Just how far north was megalodon’s range?

Anybody who has ever worked on megalodon knows that it lived in oceans virtually all over the world. Yet even a cosmopolitan distribution has limits. A recent study describing the first megalodon teeth documented from Canada seems to have found the northernmost record of the giant shark’s range in the Western Atlantic. But this has led to a somewhat surprising new disagreement in megalodon science…

Megalodon lived everywhere

Otodus megalodon, the largest shark that ever lived, needs no introduction and fascinates palaeontologists and enthusiasts for a wide variety of reasons. Of course there is the extinct shark’s gigantic size, growing over 20 m and possibly even as big as 24 m (Perez et al. 2021; Shimada et al. 2025), though there is so much more that makes megalodon interesting beyond its huge size. There’s its diet – where we know from fossil evidence it ate whales, but also know that it probably ate whatever it wanted as an opportunistic super predator, possibly eating over 90,000 kcal a day on average (Cooper et al. 2022; Godfrey & Beatty 2022; McCormack et al. 2025). There are its thermoregulatory capabilities (Ferrón 2017; Griffiths et al. 2023), something that may well have contributed to its gigantic size (Ferrón 2017; Pimiento et al. 2019). There’s its widespread use of nursery sites to ensure its offspring survived (Pimiento et al. 2010; Herraiz et al. 2020; 2026). There’s the mystery of what exactly caused its Pliocene extinction (Pimiento & Clements 2014; Pimiento et al. 2016; 2017; Boessenecker et al. 2019). But one highly noteworthy aspect to megalodon is a shockingly simple one. Its fossilised teeth have been found on every continent except Antarctica… meaning it lived virtually everywhere while it was alive (Pimiento et al. 2016).

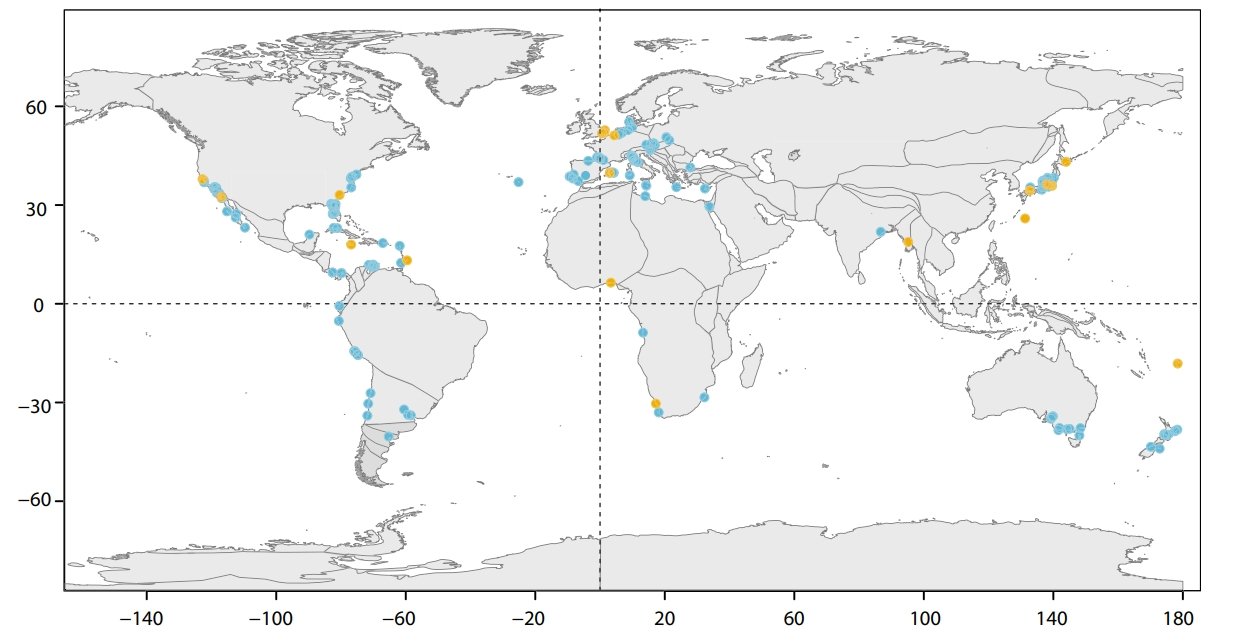

The most comprehensive study on megalodon’s geographic range was published in 2016, which conducted a meta-analysis on megalodon occurrence records from the Palaeobiology Database (PBDB); showing how its global area coverage and occupancy changed over its temporal range (Pimiento et al. 2016). Although the main purpose of this study was to investigate possible extinction mechanisms to explain these patterns, it also showcased that megalodon’s cosmopolitan distribution was captured by the PBDB, occurring along mostly coastal habitats (Figure 1; Pimiento et al. 2016).

Figure 1. Occurrences of Otodus megalodon as recorded by the PBDB in 2016. This was the map that, to my knowledge, first visualised just how widespread megalodon was. Blue dots represent confirmed fossil occurrences while yellow dots mark more dubious records. Sourced from Figure 1 of Pimiento et al. (2016).

More recent studies have identified new regions to extend that range even further or fill in gaps among the range already known. Since the 2016 study, there have been new megalodon records found in various regions where teeth are not well sampled. This has included, but is not limited to, the first teeth from Romania (Trif et al. 2016; Trif 2025), new teeth found in Spain and Portugal to the point of forming a huge regional dataset by 2026 (Reolid & Molina 2015; Herraiz et al. 2020; 2026), and the first ever megalodon tooth recorded from the Buenos Aires province in Argentina (De Pasqua et al. 2021). Perhaps even more excitingly, some of the most recent new records have been found outside of the typically coastal habitats megalodon occupied. A study from 2023 drudged up a megalodon tooth in the middle of the Pacific Ocean that showed no geological signs of transportation, indicating that the shark had been near this exact location when the tooth fell out (Pollerspöck et al. 2023). A study just published in January 2026 has further identified a second megalodon tooth from the deep sea, this one in the South Atlantic Ocean off Brazil (Baptista et al. 2026). The most likely explanation for these teeth being in such remote locations, at least in my opinion anyway, is that the sharks were almost certainly undergoing long-distance migrations, supporting a hypothesis proposed by me and my coauthors back in 2022 (Cooper et al. 2022). Whatever the reason for these occurrences, they strongly suggest that megalodon swam just about anywhere it wanted.

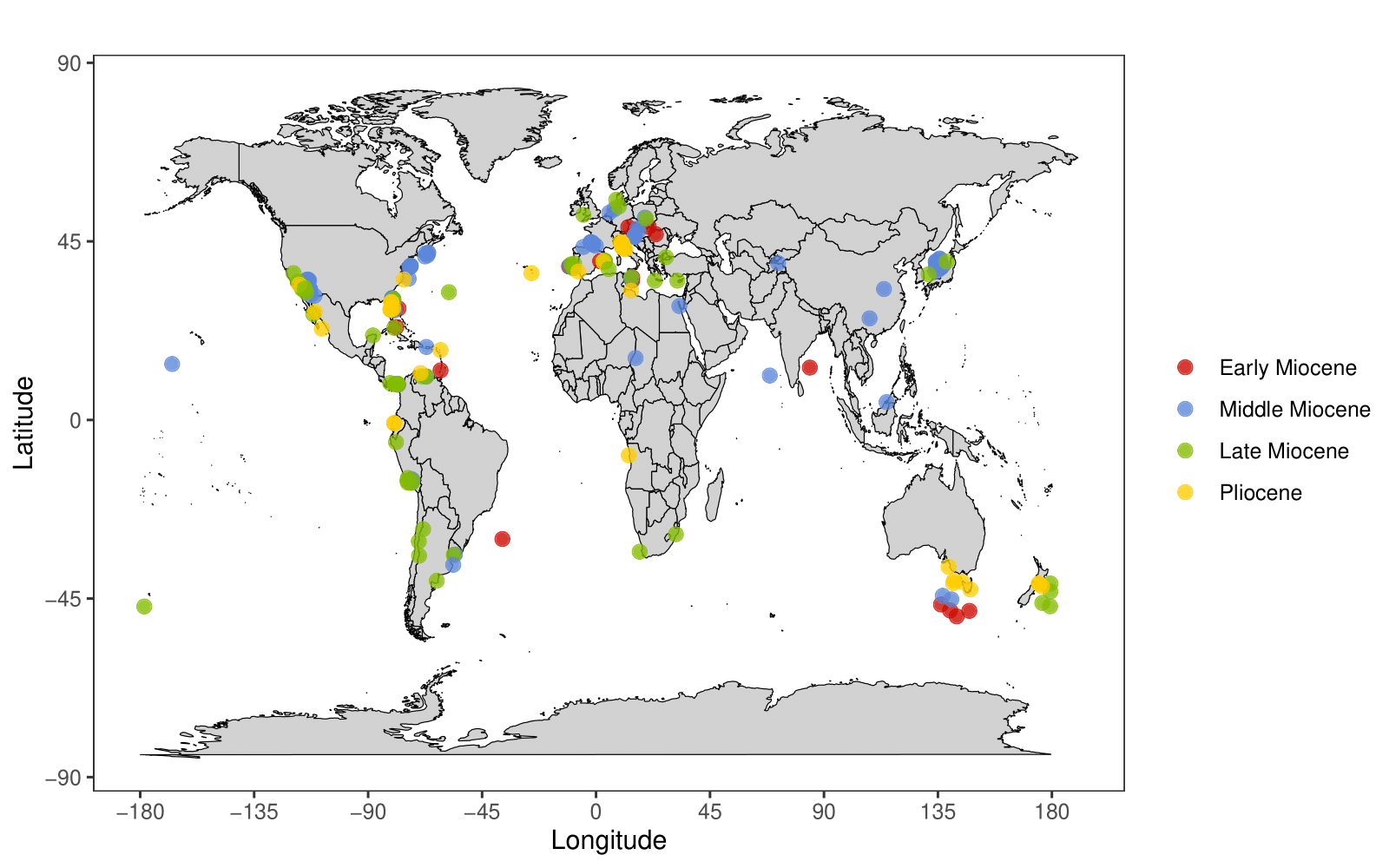

Part of the reason megalodon may have been so widespread is the fact that it was mesothermic, able to regulate its body temperature at certain body regions (Griffiths et al. 2023). It has been suggested that marine animals with such an adaptation are able to occupy wider thermal niches and therefore expand their ranges in their quest for food (Watanabe et al. 2015; but see Harding et al. 2021). Even then, however, the ocean, and indeed the planet itself, is finite. That means there was surely northernmost and southernmost range limits for megalodon. When checking and visualising megalodon records from the PBDB (as of January 2026), the southernmost records appear to come from south of Australia and New Zealand (Figure 2), with one tooth from New Zealand described over 50 years ago and recorded at a latitude of 43°S (Keyes 1972).

Figure 2. Otodus megalodon occurrences showcasing Canada as the northernmost record of the West Atlantic Ocean and Denmark as the northernmost record overall. Data are downloaded from the supplementary material of Pimiento et al. (2016), with new records since then added. These include new data from Romania (Trif et al. 2016), Indonesia (Razak & Kocsis 2018), Argentina (De Pasqua et al. 2021), the Pacific Ocean and other offshore records from the historical literature (Pollerspöck et al. 2023), the South Atlantic Ocean (Baptista et al. 2026) and Canada (Bateman & Larsson 2024). Epoch ages are based on an average over long temporal timeframes and should not necessarily be taken at face value, particularly for specimens found in the middle of the ocean.

But what about the northernmost record? A recent study (Bateman and Larsson 2024) has described new megalodon teeth and delved into the northernmost limits of the extinct giant shark’s range. Let’s have a look at that study… and the surprising debate that arose from it.

New (or rather, old) teeth from Canada

Enter Louis-Philippe Bateman. He’s a relatively new face in the field of megalodon science and grew up in eastern Canada, where he always had a keen interest in the fossil record. In fact, his final high school project was all about the fossil biodiversity of his home. It was during this early project that he came across something new. “I found out about undescribed megalodon teeth reposited in museum collections in Nova Scotia and Ontario, which were the first and only megalodon fossils from Canada,” he says.

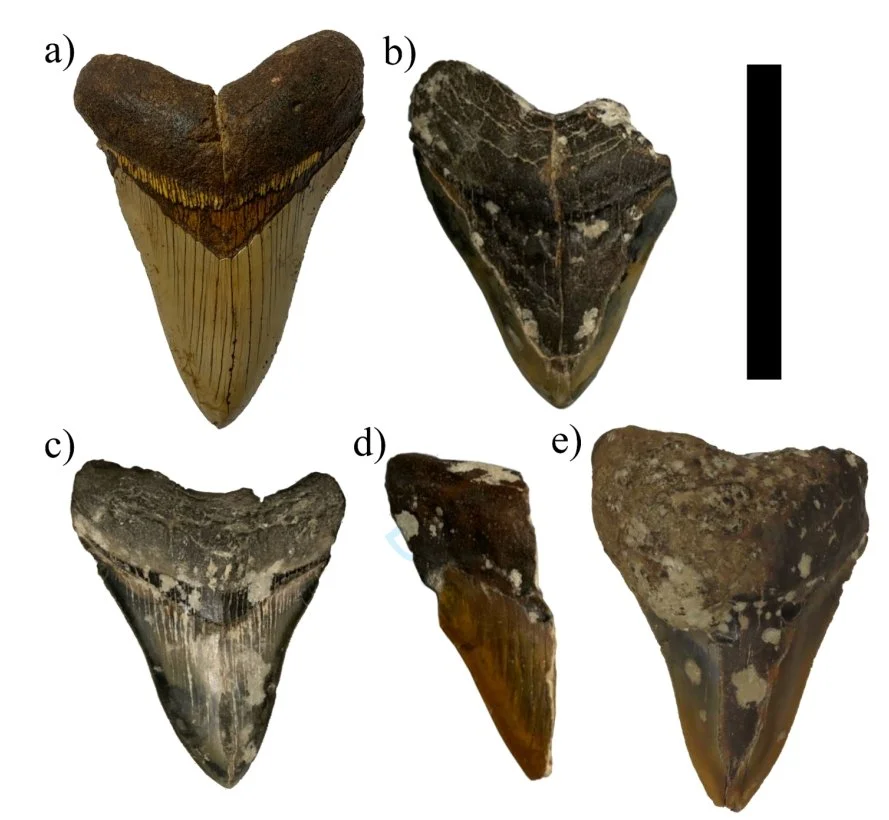

Clearly, he knew right away that these fossils, eight megalodon teeth in total (Figure 3), were special. They had been collected over the last six decades from Georges Bank, a basin in Nova Scotia consisting of both Mesozoic and Cenozoic strata. Despite being stored in museums, the teeth had never been formally described and therefore never officially entered into the scientific record. It was only during his undergraduate degree at McGill University that Louis-Philippe finally got a chance to study these teeth that had piqued his curiosity as a high schooler.

Figure 3. Five of the eight teeth described in Louis-Philippe’s study (Bateman & Larsson 2024), with the scale bar being 10 cm. Sourced from Figure 3 of Bateman & Larsson (2024).

As exciting as this was, something else stood out about these teeth and the location in which they were found. “What is notable is that only a few hundred kilometres north on the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, in submarine rocks of the same age, sampled using the same methods (as bycatch from scallop dredging), no megalodon teeth have been found,” Louis-Philippe says, “This suggests that those found on Georges Bank are the northernmost individuals of their kind in the west Atlantic.”

Working together with co-author Hans Larsson, Louis-Philippe not only provided the formal description for these teeth but identified their occurrence as being at a latitude of 42°N. This notably extended beyond previous northernmost records in the west Atlantic – a record from New Jersey at 39°N reported in Pimiento et al. (2016) and a record of 41°N reported from Martha’s Vineyard (Hitchcock 1835); famously where Jaws was filmed. Using Miocene climate modelling from an earlier paper (Burls et al. 2021), Louis-Philippe and Hans were able to recreate the likely ocean temperature at the time the giant sharks were swimming these Canadian waters.

“Using paleo-sea surface temperature maps, we were able to determine that this corresponded to a lower temperature limit of about 9.5°C,” Louis-Philippe says, “When we mapped megalodon distributions around the world, we found that the vast majority of them fell within this temperature interval.” Notably, this falls within the temperature preferences of the great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias), which is mesothermic just like megalodon and maintained a slightly lower body temperature (Goldman 1997; Griffiths et al. 2023). If we combine this information with the absence of any megalodon teeth north of Georges Bank and recent work that suggests mesothermy does not necessarily broaden thermal niche (Harding et al. 2021); then it would strongly imply that these Canadian records could well represent the northernmost records of megalodon across the western Atlantic Ocean. Indeed, the only record further north reported by Bateman and Larsson (2024) are records from Denmark at around 55°N, a record also reported by earlier papers (Bendix-Almgreen 1983; Pimiento et al. 2016).

So, what can we conclude from this? Basically, megalodon’s range may have been limited by ocean temperatures even with its mesothermic thermoregulation. This means that, according to Bateman and Larsson (2024), Canada and Denmark currently represent the northernmost range limit on each end of the Atlantic Ocean for megalodon’s reign.

Case closed, right? Well, hold that thought…

A comment and scientific debates

Now, I’m in a unique position to tell this story. It’s not just because I’m mad about megalodon, or because I’ve published papers on the big guy myself. It’s also because I reviewed Louis-Philippe’s paper first hand in 2024 (you can see my name credited in the paper’s acknowledgements). I had just passed my PhD viva at Swansea University at the time of reviewing the paper, and so it came right when my workload was reduced and I was working on my corrections. I made some suggestions in my initial review, was satisfied with the author response upon re-review, and received notification when the paper was accepted by the editor at the Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. I was pleased for Louis-Philippe in particular, who was publishing his very earliest papers at the time and had pursued this project since first reading about Canadian megalodon teeth dredged in the 1960s as a high schooler.

However, in June 2025, when I had since left Swansea, I received an invitation to review another paper at the same journal… a paper that was commenting on the original paper and had a very eye-catching title: “The northern range limit of Otodus megalodon was underestimated.”

This is where I briefly talk about scientific disagreements. They are nothing new in palaeontology. Look no further than literature on the most famous dinosaur Tyrannosaurus rex. In recent years, we’ve had debates on the number of Tyrannosaurus species (Paul et al. 2022; Carr et al. 2022) and on if we can estimate the absolute abundance of T. rex using the available evidence (Marshall et al. 2021; Griebeler 2021). Debates in shark palaeobiology happen all the time too. A fascinating 2021 study in Science looked at abundance changes in fossil shark dermal denticles and proposed an early Miocene extinction event of pelagic sharks, of which the cause remains unknown (Sibert & Rubin 2021a), which led to debates with a couple of different teams (Naylor et al. 2021; Feichtinger et al. 2021; Sibert & Rubin 2021b, c). All of these are examples of how scientists professionally air their disagreements; and are just the tip of the iceberg as to how often this happens.

Megalodon is no exception to this either. In fact, there have been multiple debates around megalodon in the last decade alone. For example, a proposal that megalodon’s family (family Otodontidae) may have been a sister family to the living family Lamnidae (containing the great white shark and makos) was met with some scepticism (Greenfield 2022a, b; Shimada 2022). There was a disagreement in the literature as to exactly when megalodon went extinct in the Pliocene (Pimiento & Clements 2014; Boessenecker et al. 2019). Most recently, a study proposing that a Spanish megalodon population may have been a case of insular dwarfism (Shimada et al. 2022), a study that was written in part due to disagreeing with prior hypotheses that megalodon used nursery sites (Pimiento et al. 2010; Herraiz et al. 2020), was criticised by a new paper that re-affirmed the presence of megalodon nurseries after all (Herraiz et al. 2026). I myself have even been on the receiving end of megalodon disagreements: following my own published works attempting to reconstruct the giant shark (Cooper et al. 2020; 2022), more recent studies argued that we cannot actually be certain of megalodon’s appearance without a complete skeleton (Sternes et al. 2022), and later re-examined vertebral column material to propose that megalodon may have been slimmer than my own works calculated (Sternes et al. 2024; Shimada et al. 2025). In many ways, the blog I wrote about the most recent of these papers just last year was a fascinating and much-needed learning experience in coming to terms with being part of such a debate. Speaking from personal experience, it can be very hard to know how to deal with it – we are all human beings who care about our work and about science after all. But at the same time, it is of utmost importance to remember not to take these things personally. Ultimately, scientific debates come from a place of wanting to ensure good science and to help advance our knowledge – and that is something all scientists should want.

Which brings us back to the comment on the Bateman and Larsson (2024) paper.

This comment was written by Tyler Greenfield. Tyler is a palaeontology student at the University of Wyoming and has had an extremely interesting career. Since the end of 2020, he has published 23 papers as of the writing of this blog. That’s an impressive number of papers for such an early career, and 20 of them were self-authored, which is perhaps even more impressive. A recurring theme throughout some of these papers is the highlighting of often overlooked historical literature. This has included correcting the record on the authorship of various sharks, including the genus name Carcharocles that has been used for megalodon (Greenfield 2020). This has also included looking at old specimens such as the infamous “Mitchell’s monster”, a specimen lost in an 1860s museum fire that may have been a baleen whale attacked by a megalodon or perhaps even a partially associated megalodon skeleton (Greenfield 2023a). Other work Tyler has conducted has included attempts to document all the skeletal remains of megalodon and its relatives – a hugely admirable task considering how rare such specimens are (Greenfield 2022a; 2022b) – and, a favourite of mine, a synthesis of all documented records claiming to be sightings of “living megalodon” and thoroughly and systematically debunking all of them (Greenfield 2023b). He has done a whole heap of other work unrelated to megalodon too, including a paper revealing that Onchopristis was a sawskate rather than a sawfish (Greenfield 2021), something that was highlighted last year in the BBC’s recent remake of “Walking with Dinosaurs”. I’ve been following Tyler’s work for years and have corresponded with him on several occasions. His passion and drive are evident in this line of work, and he has done virtually all of this without funding and in his own time. That, and his fresh angle focusing on historical literature, whatever the topic in palaeontology, I think is something many scientists should admire.

Before I discuss the comment and the response, I will briefly mention for the sake of transparency that I did reach out to Tyler to see if he would provide comments for this piece and give his full perspective; but he respectfully declined.

The comment: Does a historical record extend megalodon’s northern range limits?

Tyler’s comment on the Bateman and Larsson (2024) paper spawned from his keen eye for historical literature. By bringing attention to work published all the way back in 1910 (Hansemann 1910), he argues that the paper’s proposed northernmost range limit of 55°N (the records from Denmark) is an underestimate of megalodon’s recorded range. The 1910 paper briefly discusses a tooth belonging to megalodon that supposedly came from Adventfjorden, Spitsbergen (Greenfield 2026). This is an island in the Arctic Ocean halfway between Norway and the North Pole, located at 78°N. The tooth in question was reported by Hansemann (1910) as being up to 134 mm in “slant height” and having a “root width” of 107 mm, a clearly very large size indeed that Greenfield (2026) suggests must have come from megalodon.

This paper (Hansemann 1910) appears to have been overlooked by studies on megalodon, as it is not an occurrence recorded in the PBDB nor is it cited in other works on megalodon’s geographic range, including ones that have paid attention to historical occurrences (e.g., Pimiento et al. 2016; Pollerspöck et al. 2023). Moreover, Greenfield (2026) explains that several living sharks with mesothermy, the same physiology that megalodon had (Ferrón 2017; Griffiths et al. 2023), are more than capable of venturing into these cold waters near the North Pole. For example, the porbeagle shark (Lamna nasus), a mesotherm (Carey & Teal 1969), has been recorded as far north as 76°N (Bortoluzzi et al. 2024) and the mesothermic salmon shark (Lamna ditropis) is also known to live near the Arctic, reaching at least 65°N (Bernal et al. 2005; Hulbert et al. 2005). The comment even mentions the basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus), itself recently proposed as a mesotherm (Dolton et al. 2023), being recorded at 74°N, but cites an anonymous 2006 survey report for this (Greenfield 2026). So, if these sharks can reach Arctic latitudes, Greenfield (2026) argues that the 1910 record proves that megalodon could reach these latitudes too.

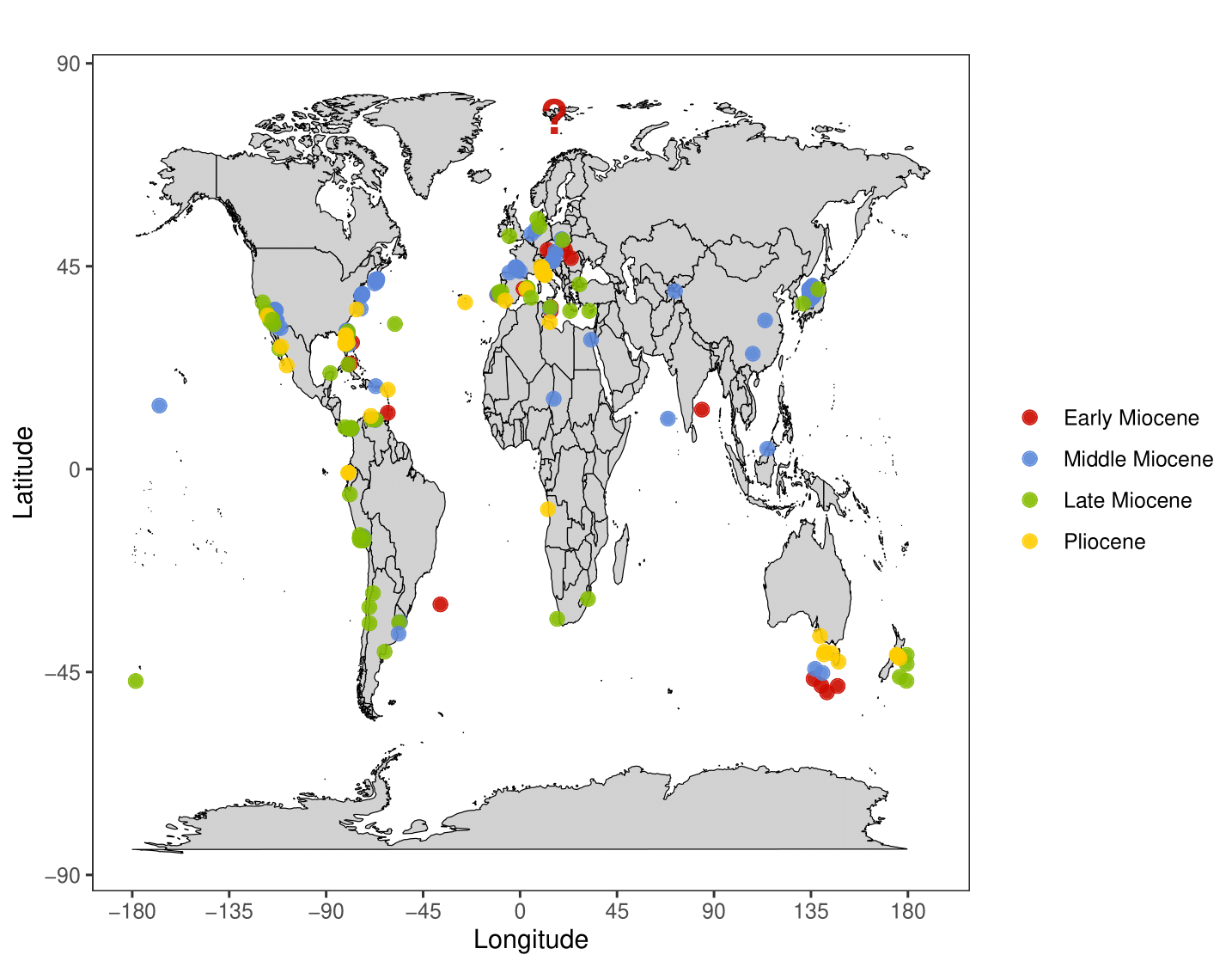

So, on paper, it seems we have a megalodon tooth found in the Arctic more than a century ago that’s gone mostly unnoticed; a tooth that would appear to extend megalodon’s northern geographic range by over 20 degrees of latitude (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Otodus megalodon occurrences, identical to Figure 2; but with a question mark highlighting the possible Hansemann (1910) record discussed by Greenfield (2026) and Bateman & Larsson (2026). Note that the tooth would be more than 20 degrees of latitude higher than the northernmost confirmed record from Denmark (Bendix-Almgreen 1983; Bateman & Larsson 2024). Beyond finding the 1910 tooth, new research attempting to find if O. megalodon lived further north than Denmark should look at fossils from Scandinavia. Epoch ages are based on an average over long temporal timeframes and should not necessarily be taken at face value, particularly for specimens found in the middle of the ocean.

The response: But can we actually verify this tooth’s existence?

There are, however, some caveats to the 1910 paper. These caveats are discussed in detail in a response by Louis-Philippe and his co-author to the comment (Bateman & Larsson 2026), but, for the sake of full transparency, some of these were things that I also picked up on during the peer review stage.

First of all, as acknowledged by the comment (Greenfield 2026), the tooth itself is not actually formally described as is standard for fossils being entered into the scientific record. There is no photograph of this tooth in the paper that could act as a figure, or even a line drawing. Indeed, the response (Bateman & Larsson 2026) states that the 1910 work (Hansemann 1910) wasn’t even peer reviewed. Most significantly, attempts to relocate this tooth have so far been unsuccessful. Hansemann was associated with the Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin, so the most likely museum repository it may have ended up in is this one (Greenfield 2026). However, despite efforts by Tyler and the curator of the museum to find the tooth in this repository, it simply hasn’t turned up. This doesn’t necessarily mean that the tooth never existed – fossils have tragically gone missing from public repositories in the past (e.g., Cooper 2025; Ceballos Izquierdo et al. 2025) – but without the official documentation, it becomes considerably harder, perhaps even impossible, to track down any trace of this specimen.

Louis-Philippe further tells me, based on his own dive into the historical literature, “The tooth itself went through the hands of at least two people before being sold to the study’s author. It is unclear exactly where the tooth had come from, except from Tertiary rubble on the island.” This makes the tooth even harder to formally describe if the exact location of where it was preserved, and therefore roughly how old the tooth was, is also difficult to trace. And there are a couple more things to consider with regards to the tooth’s resting place according to the response (Bateman & Larsson 2026). Firstly, no megalodon teeth have been found in Spitsbergen since this 1910 publication; teeth that preserve incredibly well and are usually pretty hard to miss given their size. Secondly, Louis-Philippe goes on to explain “there are no rocks of the right age to preserve megalodon on Svalbard [the Norwegian archipelago where Spitsbergen is located]. The only rocks that do preserve Cenozoic marine fossils on Svalbard are from the Paleogene.”

The Paleogene period covers the Paleocene, Eocene and Oligocene epochs; before megalodon evolved. As such, the response (Bateman & Larsson 2026) argues that it is more plausible the tooth could have belonged to one of megalodon’s Paleogene ancestors such as Otodus auriculatus or Otodus angustidens. While 78°N would still be a record northernmost occurrence for these species, the Paleogene was a considerably warmer climate than that of the Neogene and so ocean temperatures would have been higher and less restricting for the giant sharks of the time (Zachos et al. 2001; Bateman & Larsson 2026).

Finally, the response (Bateman & Larsson 2026) argues that even if the tooth did in fact come from an undiscovered Neogene area on Spitsbergen and did in fact come from a megalodon, then it would still be difficult to conclude that it is a viable population that effectively extends the shark’s range. Ultimately, a single fossil tooth cannot be considered representative of a population – especially in sharks that are losing their teeth all the time. Indeed, megalodon was almost certainly a migratory species (Cooper et al. 2022) – as supported by its teeth being found in the middle of the Pacific Ocean as well as its mostly coastal habitats (Pollerspöck et al. 2023). So, assuming we are talking about a real megalodon tooth here, it can’t be ruled out that the shark wasn’t on some long-distance migration far from its usual aggregation sites. Louis-Philippe summarises this by telling me: “It isn’t difficult to imagine some megalodons straying far north from time to time and leaving a few teeth behind. Nevertheless, we wouldn’t include these individuals as part of the normal distribution of the species.”

So, it’s fair to say that the authors of the original work are not entirely convinced by the comment. Louis-Philippe rather bluntly concludes: “this comment seems to draw a large conclusion based off little evidence. While I do think that megalodon could have lived in colder waters, I don’t think that this mysterious missing tooth is sufficient evidence to demonstrate that.”

What do I make of this latest megalodon debate?

Having peer reviewed the original paper (Bateman & Larsson 2024), and both the comment and the response (Greenfield 2026; Bateman & Larsson 2026), I am one of the few outsiders who has seen this debate play out almost in its entirety (in the professional sense anyway), and so I naturally have my own thoughts on the matter. I will try to be as balanced as possible as I do personally like and support the work of everybody involved, but I also have to take an objective lens that follows the data-driven science – and that is ultimately what forms my own opinion here and in the peer reviews I gave at the time.

There’s a theoretical side to consider. We almost certainly do not know the full extent of megalodon’s geographic range, and possibly never will. The fossil record is inherently incomplete and so we probably have many more new habitats of megalodon to discover. Even the Canadian teeth weren’t known about in the scientific record until recently despite being kept in museums for decades (Bateman & Larsson 2024). There is every possibility more teeth will be discovered that extend the extinct shark’s range limits even further north or south. Even Louis-Philippe agrees with this in principle. “I think that finding a few megalodon teeth at a much more northern or southern latitude would be a conclusive way to show that a population of individuals were living in an area, and that they had a broader thermal tolerance,” he says, “Neogene rocks in Patagonia and Antarctica would be a good place to start.”

Indeed, Tyler’s consideration towards mesothermic sharks being able to swim so far north does hold weight. Megalodon already lived basically everywhere (Pimiento et al. 2016) and was clearly capable of swimming far away from their typically coastal habitats (Pollerspöck et al. 2023; Baptista et al. 2026), so why not far north? Their body temperature was higher than today’s mesothermic sharks (Griffiths et al. 2023), which could give further credence to this scenario. It would even be vindicated if the missing 1910 tooth were to be recovered and proven to be a megalodon tooth found in the Spitsbergen area.

However, therein lies the problem: the tooth may well have existed, but as of January 2026, it is impossible to verify both where it came from and even its proposed identity as a megalodon based on what we currently have. In palaeontology, the fossils are our data. And good science needs its data to be accessible, verifiable and replicable to future researchers. Hansemann (1910) writes of a tooth that was megalodon-sized, but without any images of the tooth or the ability to locate the repository the tooth is stored in, I’m effectively just taking his word for it if I choose to believe in this. That’s not what naturally sceptical scientists are trained to do, especially for something that wasn’t peer reviewed. Simply put, if I cannot physically or digitally examine the tooth myself, then I need to show reasonable doubt as to both its proposed identity as megalodon and even its very existence.

Assuming the tooth did exist though, we could also consider one possibility not discussed in either the comment or the response. If it was indeed transferred to the Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin, and we assume this was around 1910, then the tooth could have been discarded in the century since its curation or even destroyed during World War Two. Fossils have been lost from museums before (e.g., Cooper 2025; Ceballos Izquierdo et al. 2025), but it is worth noting that the Museum für Naturkunde was severely damaged by bombing and a subsequent raid by the United States Army Air Forces on February 3rd 1945. Around 25% of the collections were destroyed and so it is feasible that the 1910 tooth could have been among the specimens lost. Nevertheless, this is undoubtedly speculation on my part and so it would still have to be verified in any search for the tooth itself. And so, this brings us back to the same problem: the burden of proof for the 1910 tooth has to be in either finding the tooth itself or any documentation about its curation in a publicly accessible repository.

There’s also the fact that there’s a suspicious lack of: (1) other megalodon teeth from Spitsbergen; (2) any verifiable rock formations dating to the Neogene in this area; and (3) a paper trail as to where this tooth came from in the first place. It appears the tooth was found by a private citizen and then passed on to at least one other person before Hansemann got hold of it (Hansemann 1910; Greenfield 2026; Bateman & Larsson 2026), which means the location in which the tooth was preserved would be almost impossible to identify with certainty even without the century between then and now. Even if we assume the tooth was local, then the Paleogene age of the rocks in the area clearly point to a megalodon ancestor as the tooth’s identity. This wouldn’t be all that surprising since ocean temperatures at this far north latitude would have been much warmer in the Paleogene than in the Neogene (Zachos et al. 2001; Bateman & Larsson 2026). Now, a size of 134 mm slant height definitely seems too big for O. auriculatus or O. angustidens, which were smaller than megalodon (Kast et al. 2022; Greenfield 2026), but without the tooth or even a scaled photo or drawing of it on hand; it is impossible to go back and verify that size for ourselves. We also have no idea if this tooth had lateral cusplets or not; the presence of which would essentially all but disprove the tooth as being megalodon as they are much more prominent in its ancestors (Perez et al. 2018; Ballell & Ferrón 2021) and otherwise only seem to occur in juvenile megalodons (Pimiento et al. 2010). Like the reported size, this also cannot be checked or verified without direct access to the tooth in question, something that is currently out of the question.

So, basically, I think it is totally possible that megalodon could well have lived further north (and also further south) than we think and was probably very much capable of swimming to high latitudes. However, the reality is that it’s also impossible to prove that with the verifiable data we currently have. As such, we should be cautious, and yes sceptical, about this “ghost fossil” from the Arctic Ocean until we can prove its identity and existence beyond any reasonable doubt.

I genuinely hope that the tooth reported from the 1910 paper can be recovered one day so we can verify it, finally describe it, and properly evaluate what it means for the science of megalodon and/or its ancestors. The implications would be huge if it were confirmed to be megalodon and that would delight me. Until then, however, we must follow the data that we currently have access to.

Acknowledgements and further reading

I thank Louis-Philippe Bateman for answering questions I had during the preparation of this piece and for fact checking an earlier version. I also thank Tyler Greenfield for correspondence.

You can read all papers involved (and make your own mind up as to the debate) in the Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences at:

Bateman LP & Larsson HCE, 2024. The first Otodus megalodon remains from Canada and their predicted range limit. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 62, 569–578.

Greenfield T, 2026. The northern range limit of Otodus megalodon is underestimated: comment on Bateman and Larsson (2025). Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 63, 1-2.

Bateman LP & Larsson HCE, 2026. Tooth be told: the case of the missing, mysterious megalodon (Otodus megalodon) tooth. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 63, 1-3.

References

Ballell A & Ferrón HG, 2021. Biomechanical insights into the dentition of megatooth sharks (Lamniformes: Otodontidae). Scientific Reports, 11, 1232.

Baptista MC, de Figueiredo Iza ERH, Cavalcanti JAD, Simões H, Palmeira LCM, de Oliveira Pessoa JC, Frazão E & Sobrinho VRS, 2026. First in situ documentation of a fossil tooth attributed of †Otodus megalodon from the deep sea of Rio Grande Rise, South Atlantic Ocean. Journal of the Geological Survey of Brazil, 9, 1-9.

Bateman LP & Larsson HCE, 2024. The first Otodus megalodon remains from Canada and their predicted range limit. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 62, 569–578.

Bateman LP & Larsson HCE, 2026. Tooth be told: the case of the missing, mysterious megalodon (Otodus megalodon) tooth. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 63, 1-3.

Bendix-Almgreen SE, 1983. Carcharodon megalodon from the Upper Miocene of Denmark, with comments on elasmobranch tooth enameloid: coronoïn. Bulletin of the Geological Society of Denmark, 32, 1-32.

Bernal D, Donley JM, Shadwick RE & Syme DA, 2005. Mammal-like muscles power swimming in a cold-water shark. Nature, 437, 1349-1352.

Boessenecker RW, Ehret DJ, Long DJ, Churchill M, Martin E & Boessenecker SJ, 2019. The Early Pliocene extinction of the mega-toothed shark Otodus megalodon: a view from the eastern North Pacific. PeerJ, 7, e6088.

Bortoluzzi JR, McNicholas GE, Jackson AL, Klöcker CA, Ferter K, Junge C, Bjelland O, Barnett A, Gallagher AJ, Hammerschlag N, Roche WK & Payne NL, 2024. Transboundary movements of porbeagle sharks support need for continued cooperative research and management approaches. Fisheries Research, 275, 107007.

Burls NJ, Bradshaw CD, De Boer AM, Herold N, Huber M, Pound M, Donnadieu Y, Farnsworth A, Frigola A, Gasson E, von der Heydt AS, Hutchinson DK, Knorr G, Lawrence KT, Lear CH, Li X, Lohmann G, Lunt DJ, Marzocchi A, Prange M, Riihimaki CA, Sarr AC, Siler N & Zhang Z, 2021. Simulating Miocene warmth: Insights from an opportunistic multi‐model ensemble (MioMIP1). Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology, 36, e2020PA004054.

Carey FG & Teal JM, 1969. Mako and porbeagle warm-bodied sharks. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology, 28, 199-204.

Carr TD, Napoli JG, Brusatte SL, Holtz TR, Hone DW, Williamson TE & Zanno LE, 2022. Insufficient evidence for multiple species of Tyrannosaurus in the latest Cretaceous of North America: A comment on “The Tyrant Lizard King, queen and emperor: Multiple lines of morphological and stratigraphic evidence support subtle evolution and probable speciation within the North American genus Tyrannosaurus”. Evolutionary Biology, 49, 327-341.

Ceballos Izquierdo Y, Orihuela J, Young MT, Sachs S, Aranda E & Viñola-López LW, 2025. What is ‘Ichthyosaurus’ torrei? Remarks on the lost holotype of a Cuban marine reptile. Historical Biology, 1-15.

Cooper JA, 2025. What we can learn from a lost fossil: the case of ‘Ichthyosaurus’ torrei. Historical Biology, 1-2.

Cooper JA, Hutchinson JR, Bernvi DC, Cliff G, Wilson RP, Dicken ML, Menzel J, Wroe S, Pirlo J & Pimiento C, 2022. The extinct shark Otodus megalodon was a transoceanic superpredator: Inferences from 3D modeling. Science Advances, 8, eabm9424.

Cooper JA, Pimiento C, Ferrón HG & Benton MJ, 2020. Body dimensions of the extinct giant shark Otodus megalodon: a 2D reconstruction. Scientific Reports, 10, 14596.

De Pasqua J, Agnolin F, Aranciaga Rolando AM, Bogan S & Gambetta D, 2021. First occurrence of the giant shark Carcharocles megalodon (Agassiz, 1843) (Lamniformes; Otodontidae) at Buenos Aires province, Argentina. Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia, 24, 141-148.

Dolton HR, Jackson AL, Deaville R, Hall J, Hall G, McManus G, Perkins MW, Rolfe RA, Snelling EP, Houghton JD, Sims DW & Payne NL, 2023. Regionally endothermic traits in planktivorous basking sharks Cetorhinus maximus. Endangered Species Research, 51, 227-232.

Feichtinger I, Adnet S, Cuny G, Guinot G, Kriwet J, Neubauer TA, Pollerspöck J, Shimada K, Straube N, Underwood C & Vullo R, 2021. Comment on “An early Miocene extinction in pelagic sharks”. Science, 374, eabk0632.

Ferrón HG, 2017. Regional endothermy as a trigger for gigantism in some extinct macropredatory sharks. PLoS One, 12, e0185185.

Godfrey SJ & Beatty BL, 2022. A Miocene cetacean vertebra showing a partially healed longitudinal shear-compression fracture, possibly the result of domoic acid toxicity or failed predation. Palaeontologia Electronica, 25, a28.

Goldman KJ, 1997. Regulation of body temperature in the white shark, Carcharodon carcharias. Journal of Comparative Physiology B, 167, 423-429.

Greenfield T, 2020. The authorship of the name of the megatooth shark Carcharocles (Lamniformes, Otodontidae). Bionomina, 20, 55-56.

Greenfield T, 2021. Corrections to the nomenclature of sawskates (Rajiformes, Sclerorhynchoidei). Bionomina, 22, 39-41.

Greenfield T, 2022a. List of skeletal material from megatooth sharks (Lamniformes, Otodontidae). Paleoichthys, 4, 1-9.

Greenfield T, 2022b. Additions to “List of skeletal material from megatooth sharks”, with a response to Shimada (2022). Paleoichthys, 6, 6-11.

Greenfield T, 2023a. The mystery of Mitchell’s monster: an Otodus megalodon skeleton, or an associated O. megalodon and whale? The Mosasaur, 13, 15-23.

Greenfield T, 2023b. Of megalodons and men: Reassessing the ‘modern survival’ of Otodus megalodon. Journal of Scientific Exploration, 37, 330-347.

Greenfield T, 2026. The northern range limit of Otodus megalodon is underestimated: comment on Bateman and Larsson (2025). Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 63, 1-2.

Griebeler EM, 2021. Dinosaurian survivorship schedules revisited: new insights from an age‐structured population model. Palaeontology, 64, 839-854.

Griffiths ML, Eagle RA, Kim SL, Flores RJ, Becker MA, Maisch IV HM, Trayler RB, Chan RL, McCormack J, Akhtar AA, Tripati AK & Shimada K, 2023. Endothermic physiology of extinct megatooth sharks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120, e2218153120.

Hansemann DP von, 1910. Demonstration eines Carcharodonzahnes aus Spitzbergen. Sitzungsberichte der Gesellschaft Naturforschender Freunde zu Berlin, 1910, 387–389.

Harding L, Jackson A, Barnett A, Donohue I, Halsey L, Huveneers C, Meyer C, Papastamatiou Y, Semmens JM, Spencer E, Watanabe Y & Payne NL, 2021. Endothermy makes fishes faster but does not expand their thermal niche. Functional Ecology, 35, 1951-1959.

Herraiz JL, Ferrón HG, Botella H, Reolid M & Martínez-Pérez C, 2026. The Iberian fossil record of †Otodus megalodon rejects Mediterranean dwarfism and supports nursery use. Biology Letters, 22, 20250640.

Herraiz JL, Ribé J, Botella H, Martínez-Pérez C & Ferrón HG, 2020. Use of nursery areas by the extinct megatooth shark Otodus megalodon (Chondrichthyes: Lamniformes). Biology Letters, 16, 20200746.

Hitchcock E, 1835. Report on the geology, mineralogy, botany, and zoology of Massachusetts. J.S. and C. Adams, Amherst, MA.

Hulbert LB, Aires‐da‐Silva AM, Gallucci VF & Rice JS, 2005. Seasonal foraging movements and migratory patterns of female Lamna ditropis tagged in Prince William Sound, Alaska. Journal of Fish Biology, 67, 490-509.

Kast ER, Griffiths ML, Kim SL, Rao ZC, Shimada K, Becker MA, Maisch HM, Eagle RA, Clarke CA, Neumann AN, Karnes ME, Lüdecke T, Leichliter JN, Martínez-García A, Akhtar AA, Wang XT, Haug GH & Sigman DM, 2022. Cenozoic megatooth sharks occupied extremely high trophic positions. Science Advances, 8, eabl6529.

Keyes IW, 1972. New records of the elasmobranch C. megalodon (Agassiz) and a review of the genus Carcharodon in the New Zealand fossil record. New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics, 15, 228-242.

Marshall CR, Latorre DV, Wilson CJ, Frank TM, Magoulick KM, Zimmt JB & Poust AW, 2021. Absolute abundance and preservation rate of Tyrannosaurus rex. Science, 372, 284-287.

McCormack J, Feichtinger I, Fuller BT, Jaouen K, Griffiths ML, Bourgon N, Maisch IV H, Becker MA, Pollerspöck J, Hampe O, Rössner GE, Assemat A, Müller W & Shimada K, 2025. Miocene marine vertebrate trophic ecology reveals megatooth sharks as opportunistic supercarnivores. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 119392.

Naylor GJ, de Lima A, Castro JI, Hubbell G & de Pinna MC, 2021. Comment on "An early Miocene extinction in pelagic sharks". Science, 374, eabj8723.

Paul GS, Persons WS & Van Raalte J, 2022. The tyrant lizard king, queen and emperor: Multiple lines of morphological and stratigraphic evidence support subtle evolution and probable speciation within the North American genus Tyrannosaurus. Evolutionary Biology, 49, 156-179.

Perez VJ, Godfrey SJ, Kent BW, Weems RE & Nance JR, 2018. The transition between Carcharocles chubutensis and Carcharocles megalodon (Otodontidae, Chondrichthyes): lateral cusplet loss through time. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 38, e1546732.

Perez VJ, Leder RM & Badaut T, 2021. Body length estimation of Neogene macrophagous lamniform sharks (Carcharodon and Otodus) derived from associated fossil dentitions. Palaeontologia Electronica, 24, a09.

Pimiento C, Cantalapiedra JL, Shimada K, Field DJ & Smaers JB, 2019. Evolutionary pathways toward gigantism in sharks and rays. Evolution, 73, 588-599.

Pimiento C & Clements CF, 2014. When did Carcharocles megalodon become extinct? A new analysis of the fossil record. PLoS One, 9, e111086.

Pimiento C, Ehret DJ, MacFadden BJ & Hubbell G, 2010. Ancient nursery area for the extinct giant shark Megalodon from the Miocene of Panama. PLoS One, 5, e10552.

Pimiento C, Griffin JN, Clements CF, Silvestro D, Varela S, Uhen MD & Jaramillo C, 2017. The Pliocene marine megafauna extinction and its impact on functional diversity. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 1, 1100-1106.

Pimiento C, MacFadden BJ, Clements CF, Varela S, Jaramillo C, Velez‐Juarbe J & Silliman BR, 2016. Geographical distribution patterns of Carcharocles megalodon over time reveal clues about extinction mechanisms. Journal of Biogeography, 43, 1645-1655.

Pollerspöck J, Cares D, Ebert DA, Kelley KA, Pockalny R, Robinson RS, Wagner D & Straube N, 2023. First in situ documentation of a fossil tooth of the megatooth shark Otodus (Megaselachus) megalodon from the deep sea in the Pacific Ocean. Historical Biology, 37, 120-125.

Razak H & Kocsis L, 2018. Late Miocene Otodus (Megaselachus) megalodon from Brunei Darussalam: Body length estimation and habitat reconstruction. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie-Abhandlungen, 299-306.

Reolid M & Molina JM, 2015. Record of Carcharocles megalodon in the Eastern Guadalquivir Basin (Upper Miocene, South Spain). Estudios Geológicos, 71, e032.

Shimada K, 2022. Phylogenetic affinity of the extinct shark family Otodontidae within Lamniformes remains uncertain—Comments on “list of skeletal material from megatooth sharks (Lamniformes, Otodontidae)” by Greenfield. Paleoichthys, 6, 1-5.

Shimada K, Maisch IV HM, Perez VJ, Becker MA & Griffiths ML, 2022. Revisiting body size trends and nursery areas of the Neogene megatooth shark, Otodus megalodon (Lamniformes: Otodontidae), reveals Bergmann’s rule possibly enhanced its gigantism in cooler waters. Historical Biology, 35, 208-217.

Shimada K, Motani R, Wood JJ, Sternes PC, Tomita T, Bazzi M, Collareta A, Gayford JH, Türtscher J, Jambura PL, Kriwet J, Vullo R, Long DJ, Summers AP, Maisey JG, Underwood C, Ward DJ, Maisch HM, Perez VJ, Feichtinger I, Naylor GJP, Moyer JK, Higham TE, da Silva JPCB, Bornatowski H, González-Barba G, Griffiths ML, Becker MA & Siversson M, 2025. Reassessment of the possible size, form, weight, cruising speed, and growth parameters of the extinct megatooth shark, Otodus megalodon (Lamniformes: Otodontidae), and new evolutionary insights into its gigantism, life history strategies, ecology, and extinction. Palaeontologia Electronica, 28, a12.

Sibert EC & Rubin LD, 2021a. An early Miocene extinction in pelagic sharks. Science, 372, 1105-1107.

Sibert EC & Rubin LD, 2021b. Response to comment on "An early Miocene extinction of pelagic sharks". Science, 374, abk1733.

Sibert EC & Rubin LD, 2021c. Response to comment on "An early Miocene extinction of pelagic sharks". Science, 374, eabj9522.

Sternes PC, Jambura PL, Türtscher J, Kriwet J, Siversson M, Feichtinger I, Naylor GJ, Summers AP, Maisey JG, Tomita T, Moyer JK, Higham TE, da Silva JPCB, Bornatowski H, Long DJ, Perez VJ, Collareta A, Underwood C, Ward DJ, Vullo R, González-Barba G, Maisch HM, Griffiths ML, Becker MA, Wood JJ & Shimada K, 2024. White shark comparison reveals a slender body for the extinct megatooth shark, Otodus megalodon (Lamniformes: Otodontidae). Palaeontologia Electronica, 27, a7.

Sternes PC, Wood JJ & Shimada K, 2022. Body forms of extant lamniform sharks (Elasmobranchii: Lamniformes), and comments on the morphology of the extinct megatooth shark, Otodus megalodon, and the evolution of lamniform thermophysiology. Historical Biology, 35, 139-151.

Trif N, 2025. A new-old occurence of the giant shark Otodus (Megaselachus) megalodon from Romania. Brukenthal Acta Musei, 19, 485-489.

Trif N, Ciobanu R & Codrea V, 2016. The first record of the giant shark Otodus megalodon (Agassiz, 1835) from Romania. Brukenthal Acta Musei, 11, 507-526.

Watanabe YY, Goldman KJ, Caselle JE, Chapman DD & Papastamatiou YP, 2015. Comparative analyses of animal-tracking data reveal ecological significance of endothermy in fishes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112, 6104-6109.

Zachos J, Pagani M, Sloan L, Thomas E & Billups K, 2001. Trends, rhythms, and aberrations in global climate 65 Ma to present. Science, 292, 686-693.