Shark Whisperer is lying to you: a look into the harmful effects of Ocean Ramsey and shark influencers

Ocean Ramsey is undoubtedly one of the most well-known “shark influencers”, whose videos show her free diving and touching wild great white and tiger sharks as she swims right up alongside them. Those videos went viral and now she has a new Netflix documentary, Shark Whisperer, platforming her to millions of viewers worldwide. Unfortunately, Ramsey’s actions are reckless, do not promote good shark conservation, and are actually harmful to sharks. Moreover, her documentary deeply and repeatedly misleads its audience. Here’s a breakdown by a shark scientist…

A viral video

It was a regular day in January 2019. I had just finished a day’s work during my masters course in palaeobiology at the University of Bristol. I was in a good mood too. Working alongside Dr Catalina Pimiento (who would go on to become my PhD supervisor) and Professor Mike Benton, I was due to begin a thesis project on none other than Otodus megalodon, the biggest shark that has ever existed (Cooper et al. 2020). It was my dream project: I had been enamoured with sharks, and particularly megalodon, since I was six years old. On top of this, I was already well-versed in shark ecology, having cage dived alongside great white sharks during internships in Gansbaai and Mossel Bay, South Africa, the prior two summers, and I was still feeling the high of having seen great white sharks up close in their natural habitats.

Alongside some of my classmates, I had gone where all the Bristol palaeobiology students went after working: down the pub. We were having pints, talking about how our projects were going, and generally just having a laugh. We’d all only known each other for about four months but lifelong friendships had been forged, and everybody already had nicknames in the big Facebook group chat. I was already known as the “shark guy” in this cohort.

About two hours into the evening, my classmate tapped me on the shoulder with his phone out.

“Have you seen this?” he asked me.

On his phone was some truly breathtaking footage that had already acquired millions of views and was appearing on news stations all over the world. A humongous great white shark, possibly as big as 6 metres long and billed on screen as “Deep Blue”, often called the largest white shark on record, was swimming calmly through the water. It was awe-inspiring to watch such a big shark majestically swimming minding her own business…

That was, until I saw a woman swimming right up in the shark’s personal space, touching it and effectively riding it, all while generating millions of clicks (Figure 1). No paper was ever published documenting this incredible shark or the behaviour she exhibited. No data were ever collected to try to understand her behaviour or how her presence might inform shark conservation. Hell, it later turned out that this shark wasn’t even “Deep Blue” at all despite her name now being thrown around to news media and millions of viewers worldwide.

This footage, like for many other people, was my introduction to Ocean Ramsey.

Figure 1: A now famous picture of Ocean Ramsey diving in 2019 alongside a large (and misidentified) great white shark.

Who is Ocean Ramsey? What is a shark influencer?

Ocean Ramsey is an author, filmmaker, model, and self-proclaimed ethologist and conservationist. I say “self-proclaimed” because her website claims that she has a bachelor’s degree in marine biology and a masters degree in ethology; however, I have yet to find any evidence of a masters thesis written by her. I even struggled to find information about exactly where she got this masters degree. This page for example mentions her studying at the University of Hawaii and supposedly getting her bachelors from San Diego State but doesn’t mention where her masters came from. I even googled for masters courses in ethology at both of these universities and found no evidence of such a course existing (Figure 2). Even her LinkedIn and Wikipedia pages have absolutely nothing about her education. Weird…

Figure 2: A search for ethology courses, which Ocean Ramsey claims to have a masters degree in, at the University of Hawaii where Ocean Ramsey claims to have studied. As you can see, when you search for this, you get no results… implying that such a course doesn’t exist. Now it could be that this is a department-level search and therefore an ethology masters was just part of a more broad department, but google also gave me back no results for this…

I should note that, yes, Ocean is her legal name. It’s not her birth name… because of course it’s not. You can actually find publicly available court documents from the Superior Court of California in San Diego of her name change back in 2004. Nevertheless, her legal name change to Ocean is, in fairness, a rather genius marketing move for her brand. It’s simple but strikingly memorable and directly associated with her activities. However, as you learn more about those activities, I also think it begins to say quite a lot about the person’s self-perception…

Ocean Ramsey is famous for diving outside a cage with large predatory sharks; namely great white sharks and tiger sharks, which are apex predators (Dedman et al. 2024). These two species are notably responsible for the highest and second highest number of shark bites on people respectively (McPhee 2014), though it should be emphasised that negative shark encounters like this are extremely rare. There are just six so-called “hotspots” of bites worldwide and even those are mainly being driven by anthropogenic conditions (Chapman & McPhee 2016). To put it simply, sharks are not out to get us, but they are still wild animals and therefore can be dangerous. Ocean, however, not only swims in the same open water as these sharks; she gets right up close and personal with them. Sometimes the shark will swim towards her but more often than not, she is the one who approaches the shark, citing a self-proclaimed “connection” with the animal. She puts her hand on them, sometimes right up near their mouths. She occasionally holds onto dorsal fins, essentially riding them; all on camera (Figure 3).

Figure 3: An image of Ocean Ramsey riding a great white shark by gripping its dorsal fin, a part of the body vital for stabilised swimming (Lingham-Soliar 2005). Such swimming could be jeopardised by Ramsey’s antics here (Martin 2007). Image taken presumably by Juan Oliphant.

This footage has gone viral during the last decade or so, leading to Ocean becoming a celebrity with over two million followers on Instagram alone. Yet curiously, despite all the interesting behaviours and individual sharks being captured in her footage – potentially valuable data for science – she has not published a single scientific paper on any of these sharks she swims with. Indeed, as far as I could find, she has co-authored exactly one paper, though not only is she not the primary author, but her exact role is not clear to me upon reading it (Blount et al. 2021). Her website claims she’s collecting data for research studies on population dynamics, photo ID, behaviour and migration patterns; yet precisely zero papers appear to have materialised from this so far. In fact, following her footage going viral, she does not appear to have started a research lab to train students and study these sharks. But she did self-publish a book, start her own courses that charge a fee of $150 per person, and even open a merch store. If that all seems like a red flag to you… that’s probably because it is.

So, how would other shark and marine scientists describe Ocean Ramsey?

Melissa Cristina Márquez is a marine scientist, science communicator and author who specialises in studying sharks and how science can guide conservation. She is also a children’s book author, a TEDx speaker, regularly writes pieces for Forbes on the latest scientific shark research, and has featured in outlets like National Geographic and the BBC. She’s even hosted Shark Week and is widely called the “mother of sharks”. Clearly, Melissa is a definitive expert in her field. She describes Ocean Ramsey as, “a social media personality who promotes close interactions with large sharks, often under the guise of conservation.”

Kristian Parton is an Exeter Marine research associate and science communicator who runs the Shark Bytes YouTube channel with over 145,000 subscribers as of September 2025. As well as his popular platform, he has conducted research into the dangerous effects of entanglement and plastic on sharks (Parton et al. 2019; 2020). He doesn’t have much praise to offer either, with his 9th most popular YouTube video describing Ocean Ramsey as “bad for sharks”. He further tells me: “There are a lot of things she claims to be that simply aren’t true.”

Mckenzie “Mckensea” Margarethe is another researcher specialising in marine ecology, marine invertebrates, fisheries and aquaculture. She is also a popular content creator who has amassed over 368,000 followers on TikTok as of September 2025, inspired by the positive impact that comes from simply teaching people about the ocean. She has given multiple talks on science communication, including at the prestigious Harvard University. Notably, she grew up on O’ahu, Hawaii, where Ocean Ramsey claims to be from, and so has met the self-proclaimed “shark whisperer” in the flesh many times. After positive introductions, Mckenzie tells me of a time when she asked Ocean about her research. “She gave me a very roundabout answer and it was not clear to me what her research was,” she says. When Mckenzie expanded her horizons and entered the world of marine science head on, she further recalls that, of all the shark scientists she met, “No one has had a positive thing to say about Ocean Ramsey.”

Perhaps the most well-known science communicator within the academic field of shark science is David Shiffman. A professor at Georgetown University and a marine conservation biologist and science writer, David has been critical of Ocean Ramsey for years. Writing for Southern Fried Scientist, in an article he has given me permission to quote, he writes, “Ocean Ramsey claims to be a shark scientist, but is not.” He elaborates further by listing: “Ocean Ramsey does not collect data, does not publish research, does not collaborate with researchers who do… and does not have research ethics permits for her activities, regularly misrepresents her own expertise and credentials, and regularly shares unequivocally factually incorrect statements about background issues related to shark biology and conservation despite being repeatedly corrected.” Not exactly a glowing endorsement.

Based on these testimonials, and my own observations of Ocean Ramsey’s activities, I think it’s most accurate to describe her as a “shark influencer”. This is somebody who films themselves swimming dangerously close to sharks with no regard for the animal’s personal space. If you type “shark influencer” into Google, Ocean Ramsey’s Instagram page is actually the first result you get. Whatever you call Ocean Ramsey, she is now the subject of a new documentary on Netflix, Shark Whisperer – a documentary that was No. 2 in the UK at the time I watched it on July 2nd 2025; two days after its premiere. This documentary is produced by “One Ocean Media” (presumably a branch of Ocean’s company “One Ocean Diving”) and features Ocean literally doing a Jesus pose underwater in the opening credits (Figure 4).

Yeah…

Figure 4: A scene from the opening credits of Shark Whisperer where Ocean Ramsey is, bizarrely, seen doing a Jesus pose underwater.

The documentary: Shark Whisperer

Set in Hawaii, the film opens with footage of a tiger shark gently cruising in the general vicinity of a free diving Ocean Ramsey while scary music plays in the background. The shark is described by Ocean as “rushing” her. Ocean is revealed to have redirected the shark without incident later in the film, but this choice of opener is a very deliberate one. It’s a classic manipulation of otherwise relatively mundane footage by documentaries to make sharks just swimming by seem more frightening to the audience. Just like how predators are often portrayed antagonistically against “cute” prey protagonists in wildlife documentaries to generate emotion from human audiences (Mills 2017), Shark Whisperer is using this “psych out” to generate an emotional response from its audience that exploits humanity’s almost-instinctual fear of sharks.

This plays into the film’s first act which details that very fear people have of sharks. Juan Oliphant, Ocean’s husband and underwater videographer, says Hawaii was seeing “lots of attacks” by sharks in his youth, yet the film references only two over an unspecified period of time. Moreover, based on data of “unprovoked attacks” from the International Shark Attack file (managed by world-leading shark expert Gavin Naylor of the Florida Museum), there have been 76 such negative shark encounters between 1828 and 2024 in all of Hawaii; and 42 in O’ahu where Ocean Ramsey is based (Figure 5). With such numbers over two centuries, those are averages of one every three to five years; hardly “lots of attacks” as the film makes out.

Figure 5: Results of all shark attacks in Hawaii from 1828 to the present recorded in Hawaii, including in O’ahu. Taken from the International Shark Attack File.

The point of making sharks look scary at the start of the film is to introduce Ocean’s mission: to show the world that sharks are not monsters. The film showcases Ocean’s dives, discusses her self-proclaimed “connection” to various individual sharks as she rides and manhandles them, and criticises shark culling and “shark finning” – a barbaric form of fishing where shark fins are removed for the dish of shark fin soup (more on these topics later). Finally, the film touches on a campaign supposedly spearheaded by Ocean and her crew to supposedly end fishing in Hawaii state waters, crediting her 2019 dive with the large great white shark (Figure 1) as the catalyst that got it passed. The bill is portrayed as a big, climatic victory for shark conservation; ultimately telling the audience that Ocean Ramsey’s antics, however reckless, are a vital part of shark conservation.

My verdict on the film

Now, I’m a shark scientist so films like this naturally pique my interest. What did I think of the film? I’ll give you my two word review right here: it’s rubbish.

Why is it rubbish? It basically comes down to three things. Firstly, the film portrays Ocean’s activities as her being “connected” to sharks; peddling that she is essentially the only person who “understands” these animals. However, the film fails to address in any meaningful way that Ocean’s antics are actually extremely harmful for sharks. The only acknowledgement is brief criticisms from the few academic researchers that do appear in the film, which are then immediately brushed over despite featuring prominently in the film’s trailer. Secondly, the film consistently misleads its audience about the science behind shark conservation. Lastly, the film ignores three pretty glaring issues about Ocean Ramsey that really ought to be considered when it comes to her role as a shark conservationist. The first of these is the harassment of marine scientists who criticise her actions. The second is her representation of “shark influencers” and the very real stupidity of these influencers that put themselves and sharks at risk. The third is the exaggeration of both how useful the Hawaii bill was for shark conservation in the grand scheme of things, and particularly Ocean Ramsey’s role in it.

I’m certainly not the only marine scientist with criticisms. Mckenzie went viral on TikTok for watching the documentary with a “bingo card” of Ocean Ramsey’s antics and has described it as little more than “a 90-minute praise piece”. She particularly lambasts the film’s presentation of Ocean herself as a messiah of sharks while ignoring the very real Hawaiian culture around sharks. “The way they framed Ocean Ramsey as a shark-hero, learning to “speak the language of the sharks” is at best very odd and at worst directly harmful to Hawai’i”, Mckenzie says, “A film based on sharks in Hawai’i should have highlighted Kanaka (Native Hawaiians) and the importance the animals have to their culture.”

Let’s break down the issues of the documentary, with the power of scientific research and citations!

Why Ocean Ramsey’s antics are bad for sharks

I want to first give the filmmakers credit where it’s due. The cinematography is undoubtedly stunning. The sharks really do look gorgeous and that speaks to Juan Oliphant’s talents as a photographer and videographer (Figure 6). It taps into making these sharks a “spectacle”, a common tactic seen even in the very best Attenborough nature documentaries. Using certain shots and music, it creates the impression that these sharks are almost otherworldly, something to be awestruck by (Ivakhiv 2013; Mills 2017). It’s an extremely effective concept of wildlife filmmaking that quickly immerses audiences in the sharks being shown on screen. This can, of course, be done from a safe distance that does not interfere with the animals, and yet, in Shark Whisperer, it is not. This is what brings us to the first big problem with Ocean Ramsey: there is utterly no need to be riding these sharks.

Figure 6: One of Juan Oliphant’s most well-known images of Ocean Ramsey diving with the large great white shark in 2019.

Simply put, what Ocean Ramsey does is wildlife harassment. And it is harmful to sharks. For example, let’s take the 2019 dive highlighted by the film. The film shows Ocean and her team getting right up in the faces of tiger sharks trying to feed on the whale carcass that eventually attracts the big great white. This interrupts sharks feeding, preventing them from obtaining a valuable source of food – one that is increasingly important to large sharks like these as they reach their biggest sizes (Fallows et al. 2013), and supports multiple shark species (Dudley et al. 2000; Lea et al. 2018), as the footage ironically shows but never acknowledges. Moreover, the film fails to mention that the viral videos of Ocean’s dive with the great white led to dozens of boats arriving around the whale carcass (Figure 7), prompting warnings to stay away from the state, and further preventing other sharks in the area from feasting on what would no doubt have been an important meal. “They’ve never acknowledged the chaos that ensued in the days after those videos were posted,” Kristian tells me, “the carcass being swarmed with snorkelers (potentially putting themselves in a dangerous situation) but also, scaring off all the damn sharks from a vital feeding opportunity!”

Figure 7: Boaters observing the carcass of the dead sperm whale fed on by the large great white shark in 2019. This is just one example of people immediately rushing towards the carcass following the viral footage, activities which disrupted shark feeding.

Perhaps most pressingly, touching, poking and riding a swimming shark like a great white or tiger shark can trigger physiological stress, often resulting in agonistic displays (Figure 8; Martin 2007; Skomal & Bernal 2010; Clua et al. 2025). This may seem aggressive on the shark’s part, but you’d be annoyed too if somebody kept prodding you while you’re just going about your day. Such stress has even been linked to shark mortality (Skomal & Mandelman 2012); in laymen’s terms – this stress can harm the shark so much it kills them. As David discusses in a CTV News interview (briefly featured in the documentary despite the crew never once contacting David himself) and his recent Southern Fried Scientist piece, such stress can also “cause pregnant sharks to spontaneously abort.” Obviously, none of this is good for the long-term survival of the sharks; yet Shark Whisperer never discusses any of it.

Figure 8: Agonistic behaviours by sharks in response to harassment by humans, sourced from Figure 6 of Martin (2007). I’ll let the original paper’s caption do the talking: “Shark–human interaction scenarios likely to elicit agonistic displays in sharks. (a) Diver approach angle and relative degree of shark agitation, represented by arrow thickness, (b) crowding a shark against the bottom, (c) crowding a shark against the bottom, a reef pinnacle, and a boat, (d) diver maintaining a 12 o’clock position above a shark's back as it swims over the bottom. Dashed circle = diver distance at which agonistic display is initiated.” Now, do any of these human behaviours around the shark look familiar?

In several scenes of Ramsey and her crew manhandling tiger sharks, we see them snap their jaws: tell-tale “agonistic displays” described in the scientific literature in response to stress or feeling threatened by humans (Martin 2007; Clua et al. 2025). This raises a harrowing question: what happens if Ocean Ramsey annoys the wrong shark and it bites her, resulting in severe injury or worse?

“Worst case scenario, Ramsey (or a colleague/customer) loses her/their life,” says Kristian. Melissa adds, “If that happens, the fallout could be immense. I'm talking a renewed fear of sharks, media frenzy, and possibly new policies that hurt sharks, not help them. It could undo decades of work to portray sharks as misunderstood animals, not monsters.”

Melissa is perhaps the best qualified to make such a prediction. Not only has she published scientific work on the public perception of sharks (Márquez et al. 2022), but, in 2018, while filming for Shark Week, she herself was bitten by a crocodile. She thankfully escaped with only a puncture scar on her left leg after the crocodile released her. Moreover, both she and the show’s producers were adamant in emphasising that this was not a malicious bite (in other words; not the crocodile’s fault). Nevertheless, people she told the story to would still ask her “did you kill it?” This is a small snippet of what could happen if Ocean Ramsey were to be harmed during her harassment of these sharks. Shark Whisperer suggests Ocean and her crew are trying to change the minds of a public calling sharks “monsters”, but such people would only be validated and emboldened if something were to go wrong during a dive. Sure, she says “don’t blame the shark” at the end of the film, but that frankly isn’t going to convince those who need to be convinced. Fear of sharks correlates with culling (Pepin-Neff & Wynter 2018) and the media fallout of a shark biting Ocean Ramsey would be widespread, likely fuelling further cullings (McCagh et al. 2015; Sabatier & Huveneers 2018; Pepin-Neff & Wynter 2018; Le Busque et al. 2021). In short, a bite or fatality during one of her dives would completely destroy the message Ocean Ramsey is supposedly trying to convey and would likely do so overnight. This is something nobody in the shark science community wants to happen.

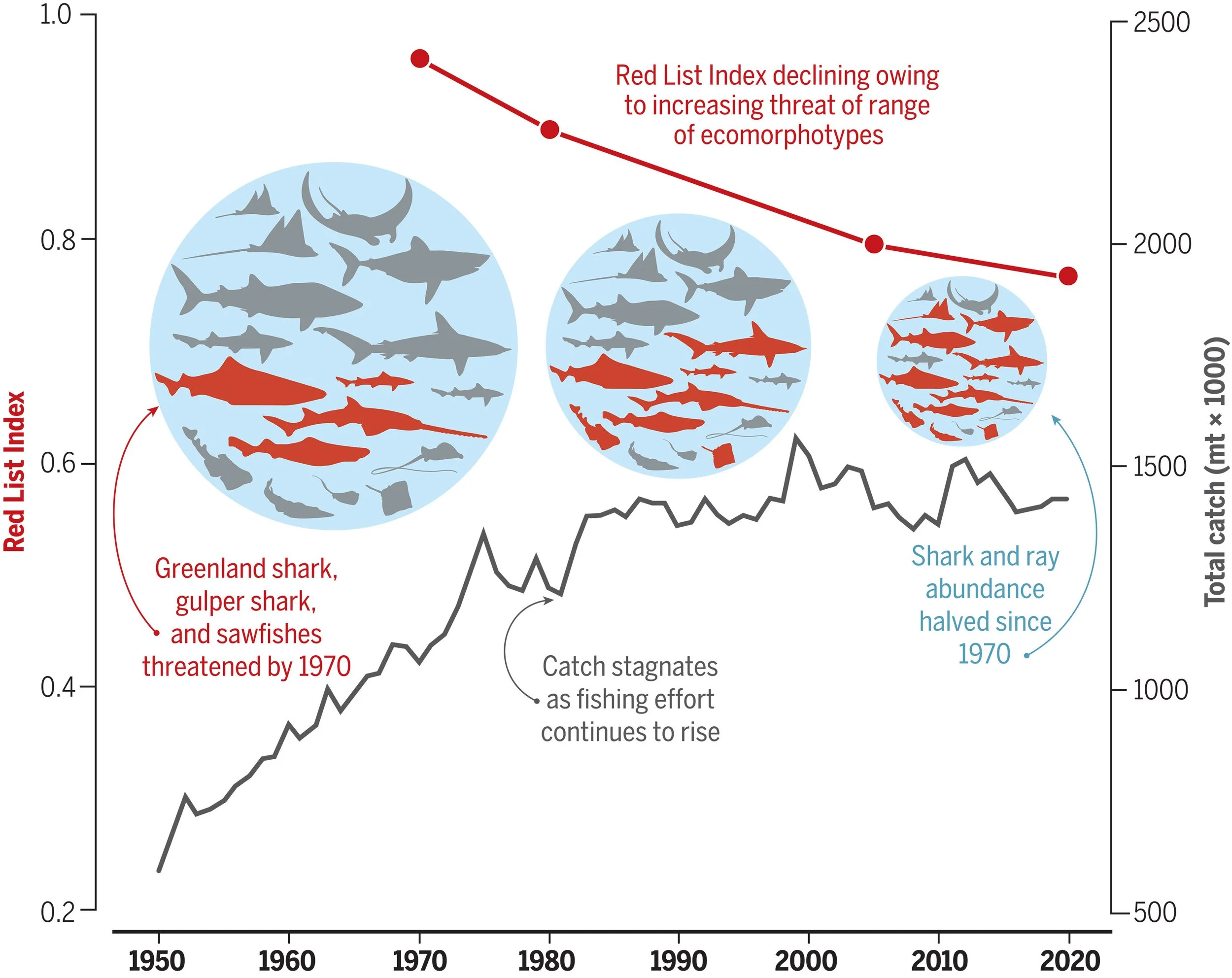

The film is quick to dismiss criticisms of Ocean Ramsey’s actions, with her insisting she’s doing good by “raising awareness”. But let’s be clear: raising awareness does not equate to solving the problem. Take the film Don’t Look Up (2021), also released by Netflix. That film’s goal was raising awareness about climate change using satire. The film was a huge conversation when it was released and was even nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture despite mixed reviews. But have you noticed that nobody talks about it anymore and climate change is still an ongoing problem that many politicians (particularly on the right wing) refuse to address? It’s not because the film was bad (it was); it’s because the release of a film “raising awareness” of course did not magically solve climate change. Relating back to sharks, you don’t need to get a selfie or ride with a shark to raise awareness for their conservation needs, and that selfie will not solve the problem: that unsustainable overfishing is causing global shark populations to collapse and threatens a third of shark species with extinction (Figure 9; Dulvy et al. 2021; 2024).

Figure 9: Total catch and global Red List Index decline of shark and ray populations from the 1950s to the 2020s. Sourced from the graphical abstract of Dulvy et al. (2024).

Ultimately, all of this is in sharp contrast to how the film portrays Ocean Ramsey as the white knight of sharks, the single biggest driving force behind studying and protecting them. Let’s just consider everything. There is no evidence she has any research ethics permits for what she does; yet there is plenty of scientific evidence that what she does to sharks harms them. If something goes wrong and she’s bitten by a shark that she’s annoyed by getting up close, her entire messaging would be instantly undone by the media fallout. Ocean and her supporters either don’t understand this or don’t care because she’s “raising awareness” and apparently that’s going to magically solve all problems sharks face. And let’s not forget what I listed in my introduction: she legally changed her name to “Ocean”; she is almost certainly profiting from the viral attention; and there is a suspicious lack of evidence behind her educational credentials.

Mckenzie provides even further insight. “She sells an online course of how to have “positive interactions with sharks”, where she teaches you how to touch them,” she says, “I think this perfectly articulates the issue. She cares more about making money than about protecting sharks.” Frankly, based on all my research for this mere blog, I agree with Mckenzie. Ultimately, Ocean Ramsey’s conduct screams a woman promoting a brand rather than meaningfully protecting sharks.

One could argue: “who cares what her credentials are or what some other scientists say behind a keyboard? She’s teaching so many people about shark science and the threats they face!” On paper, that’s not an unreasonable statement. You don’t necessarily have to be a qualified scientist to learn and teach people about a topic. If you promote good scientific information in your documentary, that’s okay right? So let’s look at the information about sharks that is promoted by Shark Whisperer… and why it’s mostly nonsense.

Misinformation peddled by the documentary

I’m going to discuss three cases of misinformation peddled by the documentary ranging from the most “forgivable” to the most brazen. Firstly, let’s again highlight the 2019 dive with the large great white shark that introduced me to Ocean Ramsey and is a key part of the documentary. When the footage went viral, the shark was branded as “Deep Blue”, often called the largest great white shark on record. The only problem is that the shark Ramsey dived with wasn’t “Deep Blue” at all. Instead, shark expert Dr Michael Domeier identified her as “Haole Girl” based on clear distinctions from “Deep Blue”. The film does not repeat the claim that the shark in 2019 was “Deep Blue” (in fact, the shark isn’t named at all), but it also fails to correct the record; something that, as far as I’m aware, Ocean Ramsey and her team have never done in the six years since the dive.

“The misidentification of an individual shark isn’t the biggest deal as far as misinformation goes, but it gives you an insight into the quick handedness and rushed nature of their social media platforms,” Kristian explains, “They were so desperate to post immediately (for clicks) that they’d swum with the (supposed) largest white shark on record, that they didn’t even bother to confirm whether it was truly that individual.”

If something this simple can be misrepresented by the documentary or the team behind it; what else do they misrepresent? Well, the supposed “connection” between Ocean Ramsey and the sharks she dives with is also a ridiculous piece of pseudoscience the documentary peddles; all in the name of what appears to be a “chosen one” narrative. Almost all the footage shows the sharks simply minding their own business, including “Haole Girl”, and Ocean Ramsey being the one swimming towards them before she rides them. Professor Kim Holland, who appears in the documentary, explains it well by saying “that shark doesn’t give a darn you’re there.”

Melissa is even more blunt. “Her actions promote a misleading narrative: that getting close to sharks equals saving them,” she says, “It doesn't.” She further adds, “Sharks aren’t dogs.”

The film is essentially “disney-fying” the sharks it features. The more technical term is “anthropomorphising”. While sharks are certainly not monsters out to get us, they are also not puppies demanding pets from humans. The film nevertheless anthropomorphises them by claiming Ocean Ramsey has some sort of connection with these wild animals. This makes the sharks characters in the story, given human-like attributes and relationships. All done to, once again, generate an emotive response from human audiences (Baker 2001; Grasso et al. 2020) rather than actually understand the ecology of these animals. This is certainly an effective technique to try to help reduce the perception of sharks as “monsters”, but it also ignores that these sharks are still wild animals and often apex predators. That is not an obstacle for the film to overcome: it is a simple fact about these large animals that should be respected.

The most frustrating bit of misinformation peddled by the documentary is the suggestion that the global population declines of sharks (Dulvy et al. 2021; 2024), are driven primarily by “shark finning” – in which fins are removed from the sharks while they are still alive and then discarded. Shark finning is undoubtedly a barbaric act, but it is simply not the biggest driver of shark declines (Shiffman 2024). Shark finning is driven primarily by east Asian nations (Dell’Apa et al. 2014; Iloulian 2016). As such, the mostly western audience of Netflix is already not contributing to shark finning and thus this focus doesn’t actually help that audience contribute to meaningful shark conservation. Mckenzie sums it up brilliantly when she tells me: “Unsustainable shark finning practices are (obviously) a huge problem but an American girl traveling to China and asking a random person (in English) what species of shark the fins are in the window for a less than 30 second segment in a documentary is not solving anything.”

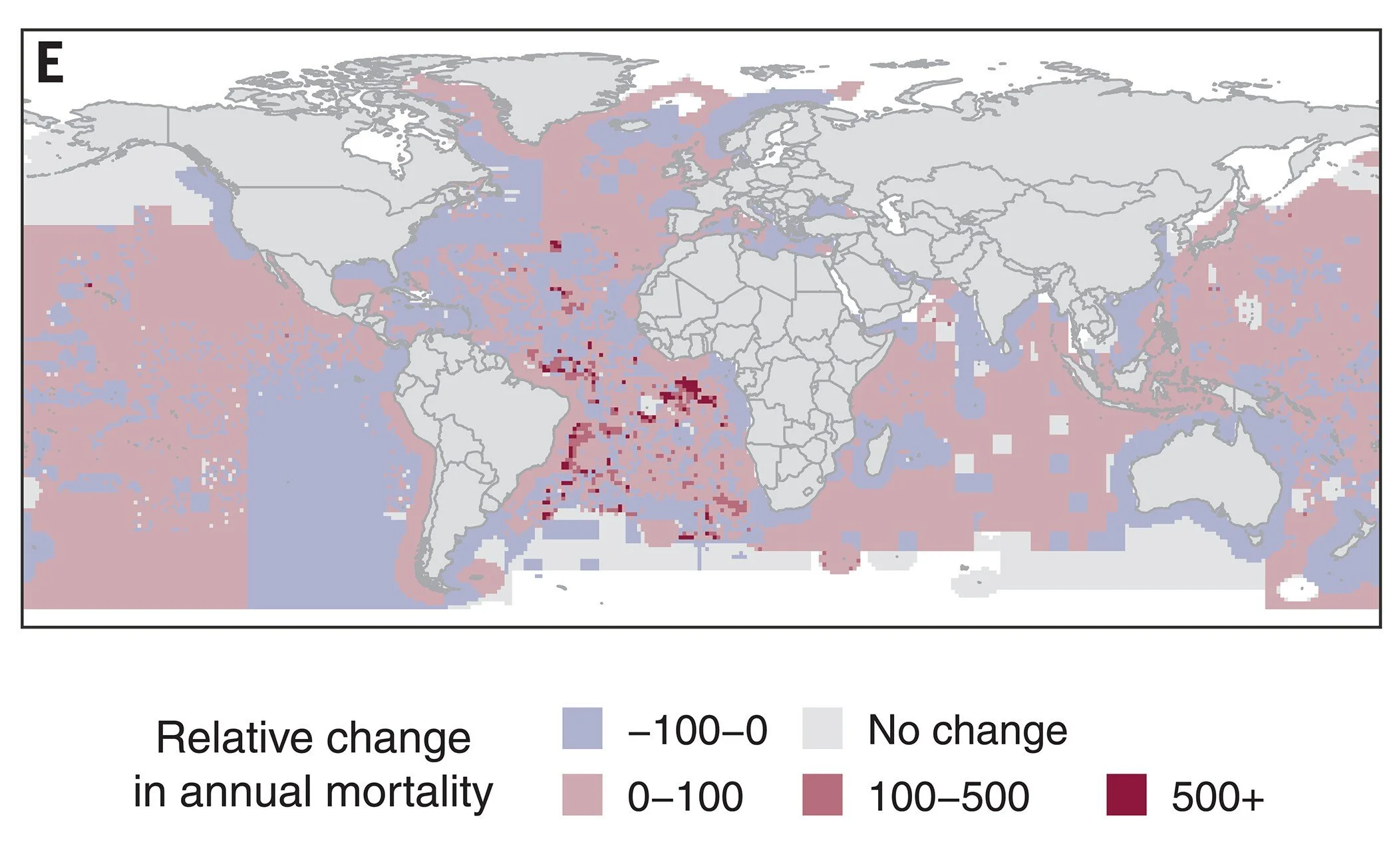

Instead, the biggest driver of shark declines is overfishing: specifically, a combination of large-scale commercial fishing and unintentional bycatch (Figure 10; Dulvy et al. 2021; 2024), something the film fails to highlight. How can your film possibly help shark conservation if you can’t even get the basic statistics behind the threats facing sharks right?

Figure 10: Sourced from Figure 3a of Dulvy et al. (2021), highlighting how overfishing (exploitation) is by far the biggest threat to sharks globally.

What makes this so frustrating is that misinformation, even from shark enthusiasts like Ocean Ramsey, is a real problem for advocating shark conservation. Despite what I’ve mentioned above, which is backed by expert scientific papers, members of the public generally believe shark finning to be the biggest cause of shark overfishing, as Ocean Ramsey’s documentary peddles (Shiffman 2024). Moreover, they are less familiar with sustainable fisheries managements that have been shown to be effective for shark conservation (Shiffman 2024). While the overfishing sharks face is a complicated issue with several complex components, it is important not to mislead your audience about what is the biggest threat. Shark Whisperer fails even in this simple task. David writes in his own piece on the documentary, “People incorrectly understanding what the problem is and what the possible solutions are does not help us to build the political support to enact a policy solution.”

Harassment of scientists and other allegations

Did you know that Ocean Ramsey’s online fans have actively harassed marine scientists for daring to criticise her antics around sharks as harmful? You’d be forgiven for not realising this because the documentary conveniently forgets to mention it.

David Shiffman highlights this in his writings about Ocean Ramsey, stating that she “coordinates massive online harassment campaigns against scientists and conservationists who criticise her”. He adds, “In 15 years on social media, I’ve never gotten more (or nastier) harassment than when I criticised her pseudoscientific nonsense. Several of my professional shark conservation advocate colleagues have gotten death threats from her supporters.”

Kristian has faced similar harassment when it comes to Ocean Ramsey. At the time of writing this piece, he has 234 videos on his Shark Bytes YouTube channel. Just two focus specifically on Ocean Ramsey and at no point in these videos does he talk about her disrespectfully. Yet, Kristian tells me, “I can’t tell you the number of harsh comments I’ve received from Ramsey fans on my YouTube channel… I have people telling me that she is more of a scientist than I am (despite me writing and conducting scientific research), that I’m sexist/misogynistic, people have called me homophobic slurs, which were deleted quickly, that I’m salty and jealous – the list could go on and on.” He even shows some of the abusive comments he received in his second Ocean Ramsey video, where even an account named after Ramsey herself appeared to respond to his first video via Reddit.

Some of Ocean Ramsey’s fans proclaim criticism of her as “sexist” as Kristian described. Yet, Mckenzie notes to me that both herself and several other women in her research groups “have received constant awful and hateful comments from her fanbase”. Moreover, Melissa, and colleagues of hers, have also received abusive comments and DMs for criticising Ramsey’s methods, something she calls “exhausting”. “It’s disheartening to be attacked for simply asking for science to guide how we talk about and interact with wildlife,” Melissa tells me.

As you can see, every single one of my interviewees for this piece, both man and woman, has received abuse for simply asking that ethical research practises be followed. That’s pretty telling.

Indeed, even following the release of this documentary, Ocean Ramsey herself wrote an article in The Times that described her critics as “jealous” (before a curious title change within two days of the article’s publication). Exactly what we are all supposed to be jealous of is unclear to me – all of us want to protect and conserve sharks; we are all doing it without foolishly risking our own safety by annoying sharks just going about their business; and my interviewees for this piece all have large platforms on social media. Even I have cage dived with great white sharks in South Africa and seen them up close (Figure 11). Funnily enough, I did not need to get out of the cage and poke them to appreciate their importance and conservation needs. Are we meant to be jealous of her fame? Because none of us go into science for fame or fortune; that’s simply not the point of conservation science. Ramsey and her fanbase’s chosen method of attack against her critics probably has something to do with the documentary choosing to portray Ramsey as a “chosen one” for protecting shark, a simply laughable concept.

Figure 11: A magical moment during one of my internships in South Africa where I locked eyes with a great white shark while chumming. The photo was taken by a tourist who captured the moment. Notice how I was able to appreciate the beauty and awe of this incredible animal (and tell tourists of shark conservation) without jumping into the sea to ride on her dorsal fin.

All in all, it’s obvious why the documentary (which I remind you was made by “One Ocean Media”) doesn’t bother to deal with any of this: because it would go against its narrative that Ocean Ramsey is the one true saviour who understands sharks. That’s yet another form of misleading the audience; and it deserves to be called out. I may well get abuse from Ramsey’s supporters for pointing this out even on my own tiny website; but this would only prove the point further. To me, it seems that Ramsey is not only lacking in the scientific department, but is unable to even contemplate the idea that she could be criticised for her actions and this (as well as, let’s not forget, her suspicious lack of evidence for her degrees and literal name change to “Ocean”) paints a picture of somebody who wants the fame rather than to be part of the collective effort to help shark conservation.

Mckenzie reflects: “I have come to realize that Ocean is unable to receive any form of criticism and will only just double down – her fanbase follows suit.”

Please influencers, for god’s sake, just stop touching the sharks

Despite the attention, and criticism, she gets, it’s worth pointing out that Ramsey is not the only “shark influencer”. And some of these other influencers have done even more stupendously stupid stunts around sharks. Several influencers swimming and posing amongst large groups of nurse sharks for clicks have been bitten while performing these stunts, as detailed in one of Kristian’s YouTube videos.

These influencers aren’t the only ones getting bitten by sharks in the name of clicks, and at least one incident has had fatal results. As detailed by Melissa in one of her pieces for Forbes, a Canadian tourist recently lost both of her hands when allegedly trying to snap a photo up close with a bull shark in the Caribbean; and a man was recently killed in Israel while trying to film sharks he had gotten into the water with. Even Shark Week had an incident when filming stunts, with the Jackass team literally jumping over bull sharks in 2021 (Figure 12). Star Sean “Poopies” McInerney (yes, he really does go by that name) failed to jump over the sharks and suffered a horrific bite on his left hand. He would eventually return to Shark Week the following year and have a rather emotional recollection of the experience before diving with sharks to face his newfound fear of sharks.

Figure 12: The poster for Jackass Shark Week, where one of the participants was bitten by a bull shark after an intentionally stupid stunt went wrong.

Call me heartless, but I struggle to sympathise with Poopies in this situation. While I have no doubt it was a terrifying experience that deeply affected him, he deliberately and intentionally jumped over wild, unpredictable, large predatory sharks and was getting in their personal space for nothing more than a cheap stunt. What did he, or indeed all the crew around him, honestly think was going to happen? It’s also hard to shake the feeling that he and the Shark Week crew sensationalised this horrific accident to simply generate more clicks and even a new documentary, all for the sake of ratings rather than education on sharks.

A 2025 study led by Dr Eric Clua identified that such bites on influencers were likely due to the sharks feeling threatened by these people getting too close (Clua et al. 2025). Indeed, Kristian recently discussed this very study on his YouTube channel, where it is suggested that influencers are a key driver of increased cases of shark bites. This is on top of the physiological stress this causes for sharks I’ve already described above (Martin 2007; Skomal & Bernal 2010; Skomal & Mandelman 2012). And of course, we have stories of retaliatory culls against sharks too in response to bites such as those mentioned above. Therefore, the scientific data are showing that this influencer behaviour is leading to people, and sharks, getting hurt and even killed.

In my opinion, the actions of all these, frankly, idiots are no different to what Ocean Ramsey does and she really ought to take some responsibility for this given her enormous platform. Or, at the very least, she should be discouraging random people who have no idea what they’re doing from copying her methods. Sadly, I have yet to see any evidence of this from her. Instead, she charges $150 for an online course on manhandling sharks on her website. Both Melissa and Kristian are in agreement with my takeaway, with Melissa stating that Ramsey “bares some responsibility” for the bites on other shark influencers and Kristian surmising “it wouldn’t surprise me if many of those who are being bitten have watched Ramsey clips before.”

Moreover, Ramsey has never shared her footage as scientific data that could potentially help sharks or at least give us new insights into them. This includes the documenting of individual sharks like the compelling story of the tiger shark “Roxy” (Figure 13) or of interesting behaviours such as “parallel swimming”. Yet no papers have ever emerged from her footage despite claims of research on Ramsey’s website. Observations of shark behaviour have led to some incredibly cool scientific work that has helped both people and sharks. A 2023 study using drones showed that juvenile great white sharks are often much closer to swimmers than they realise yet will almost always simply swim away – a clear paper that captures the rarity of shark bites and shows that sharks are not monsters all while providing valuable data (Rex et al. 2023). A 2024 study recently revealed that certain patterns on the bottom of surfboards will also reduce shark bites by playing on their vision; both fascinating work and a crucially simple step in protecting beachgoers without harming sharks (Ryan et al. 2024). Ironically, Ocean Ramsey and her crew suggest at one point in the documentary that she is turning her methods “into a science” – all evidence clearly suggests that she is not. Nor is she contributing properly to shark conservation, as the last act of Shark Whisperer claims. Let’s dissect that.

Figure 13: A tragically injured tiger shark named “Roxy”, who is featured prominently in the film. Her story is fascinating but sadly no data or scientific record have ever been made of this individual, something that would undoubtedly be valuable. Image by Juan Oliphant.

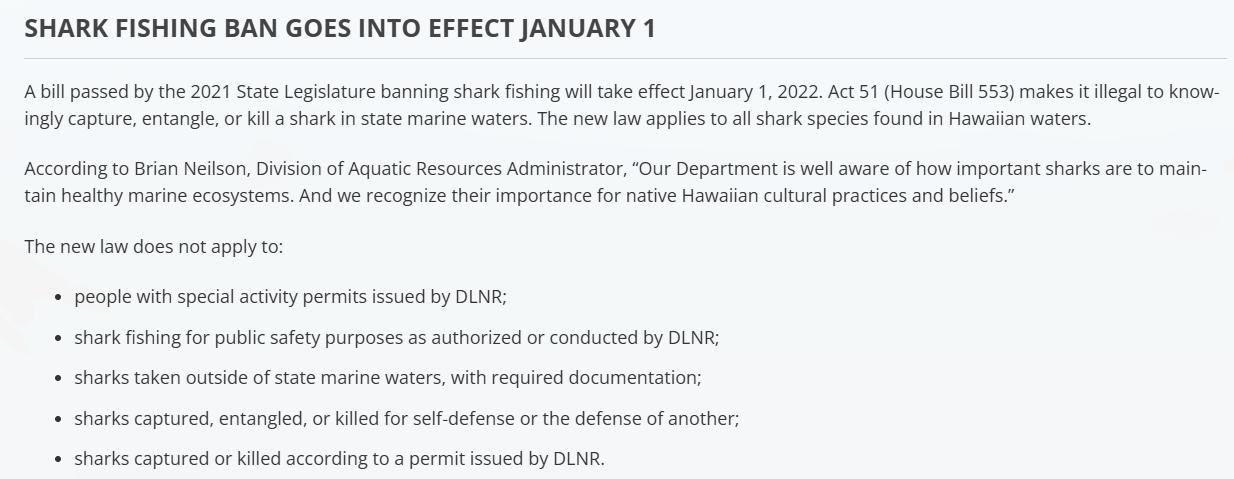

Did the Hawaii bill examined in the film actually help sharks?

The film concludes by showcasing efforts, supposedly led by Ocean Ramsey, to ban shark fishing in Hawaii in a bill that is eventually successful after her 2019 dive with “Deep Blue” – oh I’m sorry, my mistake, “Haole Girl” (see, it’s that easy to correct the record). This bill is portrayed by the documentary as a huge victory for shark conservation, only possible thanks to the efforts of the saviour Ocean Ramsey; not that this would even come close to justifying her harmful wildlife harassment. On the surface, banning shark fishing in Hawaii sounds great. Even while watching the film though, I had some questions. Namely: how is this being enforced exactly? The film never actually explains.

The other question was: did this bill really help sharks in Hawaii or in the global picture? Turns out… not really. You can read the publicly available bill right here; and its contents reveal details that the documentary omits. The bill came into effect January 1st 2022, but its ban on shark fishing applies only to state waters. It clearly states, “the new law does not apply to sharks taken outside of state marine waters” (Figure 14). In fact, it is the adjacent federal waters where the vast majority of shark fishing occurs in Hawaii. According to both David and Kristian, as much as 99.9% of shark fishing in Hawaii may occur in these waters not covered by the bill. Obviously, you cannot protect the local Hawaiian sharks if your bill banning shark fishing doesn’t actually cover the waters where most of that fishing is happening.

Figure 14: Details of the shark fishing ban in Hawaii, directly from the bill. Note where the new law does not apply.

Even the film’s own closing subtitles undermine its supposedly victorious climax. This subtitle reads that “up to 100 million sharks a year are still being killed every year”. There’s nothing inherently wrong with this statistic, which has indeed been reported in scientific literature (Worm et al. 2013). However, this is a figure the documentary also cites before the bill is passed. So clearly, those numbers have not been significantly affected by this bill. Indeed, a recent paper in Science found that fishing mortality of sharks has actually increased over the last decade despite protective actions such as this bill (Figure 15; Worm et al. 2024). Of course, it would be naïve to assume a single bill in Hawaii is doing much for global shark conservation. But the film treats it as this enormous turning point for the image and conservation of sharks, when that is simply not true. I’d therefore argue that the film is, once again, misleading its audience here.

Figure 15: Spatial changes in annual mortality of shark populations, showing increases (red), decreases (blue) or no change (grey) over the last decade. Sourced from Figure 2e of Worm et al. (2024).

But wait, there’s more! The film portrays Maui-born democratic politician and former Chair of Hawaii’s House Committee on Ocean, Kaniela Ing, in an antagonistic role – as a useless politician ignoring Ramsey’s calls for shark conservation over vindictive fishers until the 2019 dive with “Haole Girl” forces him to change his mind. This is yet more classic manipulation of the audience watching this program, and it has had very real consequences. Since the release of Shark Whisperer, Ing too has faced the wrath of Ramsey’s supporters calling him anti-shark and anti-environment online. Well, he recently wrote a piece of his own criticising the documentary for this depiction. Turns out, it was actually him who called for the bill’s hearing in the first place and moved it to a vote despite House resistance as opposed to Ocean Ramsey as the film would suggest. Indeed, it was the indigenous community that led the campaign behind the bill, despite the film clearly wanting you to believe it was all Ocean Ramsey’s doing. “Ocean has been taking credit for a bill that Indigenous community members led & pushed through,” says Melissa, rather lightly describing this hijack by Ramsey as “not cool.”

Mckenzie, herself a local to O’ahu, has even stronger feelings on the matter. “The amount of credit Ocean is getting for “passing this bill” when it was a Native Hawaiian led movement is absurd,” she tells me, “The bill wasn’t truly about shark conservation. It was Native Hawaiians protecting a sacred animal to them from a few fishermen that were causing harm. The focus was protecting a sacred animal within their waters. Now it’s been framed as Ocean’s big contribution to shark conservation, when she wasn’t even a leader within the movement. Her contributions were helpful, but she is getting far more credit than she deserves… It was egregious that Ocean was platformed as the champion for the movement in Hawaii to ban shark fishing when that was truly a Kanaka led effort.”

Ing in particular does not mince his words in criticising the documentary’s misleading narrative around the bill: “Native Hawaiians like myself—lawmakers, kūpuna (elders), and local researchers—are reduced to obstacles. We are either tokenised or vilified, while a single outsider (in this case, social media activist Ocean Ramsey) is framed as the story’s saviour. This isn’t just a misrepresentation. It reflects a deeper pattern in the way mainstream documentaries often frame their stories: who is cast as the subject, and who is cast as the object. Whose knowledge is celebrated, and whose is pushed aside.”

So, to summarise, Ocean’s campaign that serves as the conclusion to the whole film… ultimately didn’t really do anything to help sharks either in Hawaii or in the grand global scheme of things; nor was it even really her campaign. But the film misleadingly credits Ocean anyway and makes it out to be a great victory for shark conservation. This is not only lying, it is actively placing Ocean Ramsey on a pedestal of her own making.

Ing’s words are worth reflecting on. An average Joe who understandably doesn’t know a whole lot about shark conservation is going to see this film and think that things are on the up for sharks thanks solely to Ocean Ramsey and her cohort. This not only ignores indigenous stories of coming out to support sharks even in this small way; but the reality is that the stats of shark fishing mortality, as reported by Worm et al. (2024), are much grimmer than they were prior to the Hawaii bill (Figure 14, 15).

Netflix has a public service responsibility to do proper research and report the facts when it makes documentaries like this, particularly when they’re supposedly about conservation. But this evidently wouldn’t fit the film’s narrative of Ocean Ramsey being this “chosen one” for saving sharks. So, instead, they make her campaign’s success out to be far bigger for shark conservation than it actually was and overlook the role of indigenous people in getting even this small bill passed. This is blatant manipulation of the viewing public and is particularly disappointing to see from its director James Reed, who won an Oscar for his earlier nature documentary My Octopus Teacher. Whether Netflix’s producers and/or researchers were unaware of Ramsey’s misrepresentations of science, people, and herself; or whether they chose to ignore them because they liked the film’s narrative, it really doesn’t matter because both are shockingly bad for science communication and the same problem arises either way.

You want to make a documentary portraying sharks more positively? Fantastic; I want to see more of that too. But don’t manipulate your audience to get the result you want. That is not good science communication, it’s not good entertainment, and it’s not good for the sharks.

Studios are no stranger to misinformation of sharks… or science in general…

Unfortunately, studios making shark-based films have always been prone to misinformation and irresponsible messaging, with Ocean Ramsey hardly being the only person to blame here. The world-famous Shark Week is, tragically, a glutton for misinformation on sharks these days. A 2022 study that David co-authored has shown evidence that Shark Week widely contributes to the generally negative public perception of sharks (Whitenack et al. 2022). Moreover, I don’t think I even need to discuss Megalodon: the monster shark lives (2013), a Shark Week program that cast actors as scientists and deliberately misled its audience into believing that it was a documentary about the modern-day survival of Otodus megalodon, the gigantic shark that has been extinct for over 3 million years (Pimiento & Clements 2014; Boessenecker et al. 2019). Just to be clear: there is no evidence for megalodon’s survival: with all anecdotal reports of living individuals recently being debunked in the scientific literature (Greenfield 2023).

Even Netflix, the service distributing Ramsey in the new documentary, is sadly not immune to platforming pseudoscientific nonsense. To name one example, look no further than the mind-numbingly dreadful miniseries MH370: The Plane That Disappeared (2023) (Figure 16). For those who don’t remember, Malaysian Airlines Flight 370 (MH370) was a passenger plane that, in 2014, vanished in the middle of the night while flying from Kuala Lumpur to Beijing with 239 people on board. We don’t know why it disappeared as the fuselage has never been found as of 2025. However, the combination of military radar data and some very clever scientists using “ping” communications with Inmersat satellites were able to determine that the plane had its transponder switched off before it turned around and flew for over seven hours thousands of miles off course before crashing somewhere in the southern Indian Ocean (Ashton et al. 2015). This was then positively confirmed by the eventual emergence of debris washed up in eastern Africa; debris that was definitively identified as coming from MH370 based on serial numbers and other identifying features (Trinanes et al. 2016).

Despite this concrete, undeniable, evidence, the Netflix documentary about this plane spends two of its three episodes promoting utterly nonsensical conspiracy theories by two armchair “experts”. The first, Jeff Wise, is an American journalist who promotes a theory (with no evidence) that Russian spies somehow hacked the plane, shut off its oxygen supply without dying themselves, and redirected the plane north while somehow manipulating the Inmersat data (which nobody knew at the time could track planes; Ashton et al. 2015) to throw off authorities. He has essentially invented a Mission: Impossible style heist as the theory he publicly promotes based on nothing but “I’m just asking questions”, a typical strawman argument you see in conspiracy theory loonies from COVID deniers to those who disbelieve the moon landing. Between this baseless theory of a real tragedy and allegations that Wise has harassed family members of MH370 victims, one might be tempted to submit Wise as a contender for, as South Park might say, “the biggest douche in the universe”.

The second armchair expert of the program was Florence de Changy; a French journalist who insists that the Americans shot down the plane. Again, this is based on no evidence, but instead mysterious “sources” that she never elaborates on; sources she is definitely not just making up to sell a book she’s written about MH370. Of course, both Wise and de Changy conveniently ignore the scientific evidence contradicting them, and a sensible viewer will dismiss their theories for the rubbish that they are. In my opinion, these two people do not care about the victims of this missing plane or about finding out what actually happened, but are instead using it for nothing more than attention. The point of this tangent is that because Netflix has platformed these conspiracy theorists who are not helping solve the wider problem, they now have an audience of millions who might watch them and believe their rubbish.

Figure 16: The poster for Netflix’s MH370: The plane that disappeared (2023), another case study of a Netflix documentary platforming absolute rubbish and not solving the wider issue being addressed. Might actually be the worst documentary I’ve ever watched.

I would argue that Ocean Ramsey is to sharks what Jeff Wise or Florence de Changy are to MH370 – proclaiming that her videos are in support of sharks and helping their conservation yet at the same time harassing the actual scientists who tell her of the dangers of her antics and consistently misrepresenting the very real threats shark face and the science that can help them.

The positive side of shark documentaries

I’m not here to gatekeep and say that only qualified shark scientists can help sharks because that’s both unhelpful and not true. Media is actually one of the most powerful tools we have and that comes down to talented filmmakers and a compelling story to tell from the science. Think about how Blackfish (2013) or Free Willy (1993) made audiences care about orcas in captivity. While negative press or media of sharks certainly aren’t causing the population declines sharks face today, nor the overfishing responsible, it does mean that regular people I meet (speaking only to my own experience) mostly don’t care about sharks enough to want to help conserve them. Awe-inspiring footage of sharks in their natural habitats or even new works of fiction simply not portraying them as monsters, but just as the complex and fascinating animals they are, could be one of the best and mostly unexplored ways we could help rebrand sharks to make people want to help them.

However, this needs to be done responsibly. And Ocean Ramsey’s way of doing it is just not responsible, nor is it promoting the science that is trying to help sharks. So, if her ways aren’t helpful; what can media do to rebrand sharks in a more positive light or promote their conservation needs?

Well, one YouTuber immediately springs to my mind. Meet Carlos Gauna, AKA “The Malibu Artist”. He too films great white sharks in their natural habitats for his YouTube channel with over 280,000 subscribers. However, he has several crucial differences from Ocean Ramsey. Namely, he films the sharks using drones – at no point interfering with these wild animals. Moreover, he shares this footage with shark scientists, with one observation of an unusually white great white shark (Figure 17) even being the subject of a paper he published alongside Dr Phil Sternes (Gauna & Sternes 2024). Indeed, a recent video by Carlos and Phil has hinted at further papers down the line (one of which was published in September 2025; Gauna & Sternes 2025). This is all possible because, unlike Ramsey, Carlos shares his data with scientists.

Figure 17: A small and unusually white great white shark filmed by a drone off the California coast. The white film on its body is hypothesised as either a skin condition or uterine milk, implying this individual may be a fresh newborn. Whatever the case, this important observation was possible with a drone without invading the shark’s space. Images by Carlos Gauna. Sourced from Figure 1 of Gauna & Sternes (2024).

There are also plenty of good shark documentaries that promote data-driven shark science and conservation. A particularly good one is Shark (2015), narrated by Paul McGann of Doctor Who, which spotlights many smaller, lesser-known shark species as well as the famous ones like great whites and tiger sharks. A fantastic recent documentary that did not focus only on sharks was Oceans with David Attenborough (2025), which powerfully spotlights the importance of our oceans and the destruction they are facing under unsustainable overfishing, even taking time to mention the dangers sharks are facing with striking visuals and clear, understandable scientific data (Figure 18). It’s one of the best and most important films of 2025 and I recommend any and all readers to seek it out.

Figure 18: The poster for Ocean with David Attenborough (Silverback Films). I cannot recommend this film enough for its strength in highlighting the dangers of overfishing to the entire ocean, including sharks. I can only do so much justice to the film, so if you want a full break down, you can read this review here instead.

Even works of fiction, I believe, could be a powerful tool for not only portraying sharks as animals rather than monsters; but highlighting their importance to our oceans as dictated by the science. An interesting analysis using IMDB (the internet movie database) recently found that, of all fiction films up to 2021 featuring sharks, just one did not portray sharks negatively at any point. That film: Finding Dory (2016), which notably featured the loveable Destiny the whale shark rather than a large predatory shark like the great white (Le Busque & Litchfield 2022). Remember, even the delightful great white, Bruce, who deemed “fish are friends, not food!” in the original Finding Nemo (2003), still tried to kill our protagonists after smelling blood. Books are also a chance for this relatively unexplored fictional realm. Melissa wrote and published Mother of Sharks in 2023; a powerful and deeply personal children’s book that explores her childhood fascination with the ocean that ultimately drove her to pursue a career in shark conservation.

A piece of fiction portraying sharks as the complex wild animals that they are, but importantly not the monsters they are so often seen as, is something that I believe has not really been tackled. In fact, I myself am currently writing and experimenting with a fiction novel dealing with this very topic, but that’s for another day.

And guess what? All of this is working towards exactly the same aims Ocean Ramsey claims to have, but without getting up in the shark’s face and annoying it. Let all of that sink in.

Concluding remarks

If there is one thing that I unequivocally agree with Ocean Ramsey about, it is this: sharks are not monsters. They are simply animals: beautiful, majestic and inspiring animals that have lived in our oceans for over 400 million years. They deserve our respect and protection. But they are also not playthings or props for influencers. They are wild animals. That is something we must respect in our understanding of sharks.

I really want to give Ocean Ramsey the benefit of the doubt despite all of what I’ve described above. Believe it or not, there’s still a part of me that believes she genuinely does care about sharks. But I am also not convinced of her sincerity. I simply cannot shake the feeling that sharks are mostly tools for her brand now reaching enormous Netflix and social media audiences. Whatever the case, such a platform comes with a responsibility to promote the science accurately and not mislead audiences. That is something Shark Whisperer consistently fails to do, and this makes it a terrible documentary (Figure 19).

Figure 19: The documentary in question. Takeaway: it is lying to you and it is a rubbish film.

So let me reiterate one last time. Harmful harassment of sharks is not the answer to the extinction risks they face. Misinformation about shark conservation is not the answer and will only hurt sharks (Shiffman 2024). Harassing scientists who call out your actions as harmful to sharks because their expertise goes against your saviour complex is not helping the sharks either. And exaggerating your involvement in conservation bills over indigenous people, and possibly lying about your own credentials, is just suspect behaviour. Sadly, all of this points to somebody who’s in it more for fame than they are for science-driven conservation of sharks; which are some of Earth’s oldest and most threatened animals (Dulvy et al. 2021; 2024; Pimiento et al. 2020; 2023).

David puts it best in his recent piece. “The number one threat to sharks is unsustainable overfishing,” he writes, “and unsustainable overfishing is not fixed by videos of people riding sharks.” But perhaps an even more appropriate way to wrap up this piece is to simply share with you a potent quote from a native Hawaiian, the Maui-born Kaniela Ing, a person unfairly and misleadingly villainised in Shark Whisperer, from his own recent writings:

“Shark Whisperer claims to honour marine life, but it often confuses reverence with control,” he writes, “It reduces wild, sacred beings to characters in a human-centred story, mistaking closeness for connection. But in our culture, true respect often means keeping a sacred distance. Not everything powerful needs to be tamed. Every creature holds its own essence and role in the web of life, whether or not it reflects us. To honour them is to let go of the need to dominate or display, and simply let them be.”

Acknowledgements

I deeply thank Melissa Cristina Márquez, Kristian Parton and Mckenzie Margarethe for agreeing to take part in this piece. They were all very generous in answering my many, many questions on this topic that they have no doubt had to address many times in their careers. I am also grateful to David Shiffman for permitting me to quote his own writings, and Kaniela Ing for permission to quote directly from his article as well, granted to me indirectly through Mckenzie. David, Kristian and Mckenzie are further thanked for fact checking an earlier version of this piece, and for doing so even in spite of its length. My brother Calum, a Rotten Tomatoes approved media critic and writer, also proofread this piece, and I thank him for giving me insight into techniques of spectacle and anthropomorphism used in nature documentaries. Finally, I thank my dear partner Freddie for her constant support and her belief in my own drive to help sharks.

You can follow David’s articles in Southern Fried Science at: https://www.southernfriedscience.com/author/whysharksmatter/. Here’s the article he himself wrote about the documentary: https://www.southernfriedscience.com/what-ocean-ramsey-does-is-not-shark-science-or-conservation-some-brief-thoughts-on-the-shark-whisperer-documentary/.

You can follow Melissa’s articles in Forbes on new shark papers (including some of mine!) at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/melissacristinamarquez/.

You can watch and follow Kristian’s YouTube channel Shark Bytes at: https://www.youtube.com/@SHARKBYTES.

You can watch and follow McKenzie on TikTok at: https://www.tiktok.com/@mckensea?lang=en.

You can watch and follow incredible white shark footage (from a suitable distance that does not harass the sharks) by Carlos Gauna on The Malibu Artist YouTube channel at: https://www.youtube.com/@TheMalibuArtist.

References

Ashton C, Bruce AS, Colledge G & Dickinson M, 2015. The search for MH370. The Journal of Navigation, 68, 1-22.

Baker S, 2001. Picturing the beast: Animals, identity, and representation. University of Illinois Press.

Blount C, Pygas D, Smith MPL, McPhee DP, Bignell C & Ramsey O, 2021. Effectiveness against white sharks of the rpela personal shark deterrent device designed for surfers. Journal of Marine Science and Technology, 29, 582-591.

Boessenecker RW, Ehret DJ, Long DJ, Churchill M, Martin E & Boessenecker SJ, 2019. The Early Pliocene extinction of the mega-toothed shark Otodus megalodon: a view from the eastern North Pacific. PeerJ, 7, e6088.

Clua EE, Vignaud T & Wirsing AJ, 2025. The Talion law “tooth for a tooth”: self-defense as a motivation for shark bites on human aggressors. Frontiers in Conservation Science, 6, 1562502.

Cooper JA, Pimiento C, Ferrón HG & Benton MJ, 2020. Body dimensions of the extinct giant shark Otodus megalodon: a 2D reconstruction. Scientific Reports, 10, 14596.

Chapman BK & McPhee D, 2016. Global shark attack hotspots: Identifying underlying factors behind increased unprovoked shark bite incidence. Ocean & Coastal Management, 133, 72-84.

Dedman S, Moxley JH, Papastamatiou YP, Braccini M, Caselle JE, Chapman DD, Cinner JE, Dillon EM, Dulvy NK, Dunn RE, Espinoza M, Harborne AR, Harvey ES, Heupel MR, Huvenners C, Graham NAJ, Ketchum JT, Klinard NV, Kock AA, Lowe CG, MacNeil MA, Madin EMP, McCauley DJ, Meekan MG, Meier AC, Simpfendorfer CA, Tinker MT, Winton M, Wirsing AJ & Heithaus MR, 2024. Ecological roles and importance of sharks in the Anthropocene Ocean. Science, 385, adl2362.

Dell’Apa A, Chad Smith M & Kaneshiro-Pineiro MY, 2014. The influence of culture on the international management of shark finning. Environmental Management, 54, 151-161.

Dudley SF, Anderson-Reade M, Thompson GS & McMullen PB, 2000. Concurrent scavenging off a whale carcass by great white sharks, Carcharodon carcharias, and tiger sharks, Galeocerdo cuvier. Fishery Bulletin, 98, 646-649.

Dulvy NK, Pacoureau N, Matsushiba JH, Yan HF, VanderWright WJ, Rigby CL, Finucci B, Sherman CS, Jabado RW, Carlson JK, Pollom RA, Charvet P, Pollock CM, Hilton-Taylor C & Simpfendorfer CA, 2024. Ecological erosion and expanding extinction risk of sharks and rays. Science, 386, eadn1477.

Dulvy NK, Pacoureau N, Rigby CL, Pollom RA, Jabado RW, Ebert DA, Finucci B, Pollock CM, Cheok J, Derrick DH, Herman KB, Sherman CS, VanderWright WJ, Lawson JM, Walls RHL, Carlson JK, Charvet P, Bineesh KK, Fernando D, Ralph GM, Matsushiba JH, Hilton-Taylor C, Fordham SV & Simpfendorfer CA, 2021. Overfishing drives over one-third of all sharks and rays toward a global extinction crisis. Current Biology, 31, 4773-4787.

Fallows C, Gallagher AJ & Hammerschlag N, 2013. White sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) scavenging on whales and its potential role in further shaping the ecology of an apex predator. PLoS One, 8, e60797.

Gauna C & Sternes PC, 2024. Novel aerial observations of a possible newborn white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) in Southern California. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 107, 249-254.

Gauna C & Sternes PC, 2025. Drone observations reveal white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) dorsal fins are highly flexible and possible investigatory structures. Journal of Fish Biology, 1-4.

Grasso C, Lenzi C, Speiran S & Pirrone F, 2020. Anthropomorphized nonhuman animals in mass media and their influence on human attitudes toward wildlife. Society & Animals, 31, 196-220.

Greenfield T, 2023. Of Megalodons and Men: Reassessing the ‘modern survival’ of Otodus megalodon. Journal of Scientific Exploration, 37, 330-347.

Iloulian J, 2016. From shark finning to shark fishing: A strategy for the US & EU to combat shark finning in China & Hong Kong. Duke Environmental Law & Policy Forum, 27, 345.

Ivakhiv AJ, 2013. Ecologies of the moving image: Cinema, affect, nature. Wilfrid Laurier Press.

Le Busque B, Dorrian J & Litchfield C, 2021. The impact of news media portrayals of sharks on public perception of risk and support for shark conservation. Marine Policy, 124, 104341.

Le Busque B & Litchfield C, 2022. Sharks on film: An analysis of how shark-human interactions are portrayed in films. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 27, 193-199.

Lingham‐Soliar T, 2005. Dorsal fin in the white shark, Carcharodon carcharias: a dynamic stabilizer for fast swimming. Journal of Morphology, 263, 1-11.

Márquez MC, Boyle A, Brown K, Elcock JN & Kitolelei S, 2022. Public perceptions of sharks. In Minorities in Shark Sciences (pp. 1-34). CRC Press.

Martin RA, 2007. A review of shark agonistic displays: comparison of display features and implications for shark–human interactions. Marine and Freshwater Behaviour and Physiology, 40, 3-34.

McCagh C, Sneddon J & Blache D, 2015. Killing sharks: The media’s role in public and political response to fatal human–shark interactions. Marine Policy, 62, 271-278.

McPhee D, 2014. Unprovoked shark bites: are they becoming more prevalent? Coastal Management, 42, 478-492.

Mills B, 2017. Animals on television: the cultural making of the non-human. Palgrave Macmillan.

Parton KJ, Galloway TS & Godley BJ, 2019. Global review of shark and ray entanglement in anthropogenic marine debris. Endangered Species Research, 39, 173-190.

Parton KJ, Godley BJ, Santillo D, Tausif M, Omeyer LC & Galloway TS, 2020. Investigating the presence of microplastics in demersal sharks of the North-East Atlantic. Scientific Reports, 10, 12204.

Pepin‐Neff C & Wynter T, 2018. Shark bites and shark conservation: an analysis of human attitudes following shark bite incidents in two locations in Australia. Conservation Letters, 11, e12407.

Pimiento C, Albouy C, Silvestro D, Mouton TL, Velez L, Mouillot D, Judah AB, Griffin JN & Leprieur F, 2023. Functional diversity of sharks and rays is highly vulnerable and supported by unique species and locations worldwide. Nature Communications, 14, 7691.

Pimiento C & Clements CF, 2014. When did Carcharocles megalodon become extinct? A new analysis of the fossil record. PLoS One, 9, e111086.

Pimiento C, Leprieur F, Silvestro D, Lefcheck JS, Albouy C, Rasher DB, Davis M, Svenning JC & Griffin JN, 2020. Functional diversity of marine megafauna in the Anthropocene. Science Advances, 6, eaay7650.

Rex PT, May III JH, Pierce EK & Lowe CG, 2023. Patterns of overlapping habitat use of juvenile white shark and human recreational water users along southern California beaches. PLoS One, 18, e0286575.

Ryan LA, Gennari E, Slip DJ, Collin SP, Peddemors VM, Huveneers C, Chapuis L, Hemmi JM & Hart NS, 2024. Counterillumination reduces bites by Great White sharks. Current Biology, 34, 5789-5795.

Sabatier E & Huveneers C, 2018. Changes in media portrayal of human-wildlife conflict during successive fatal shark bites. Conservation and Society, 16, 338-350.

Shiffman DS, 2024. The Causes and Consequences of Public Misunderstanding of Shark Conservation. Integrative and Comparative Biology, 64, 171-177.

Skomal GB & Bernal D, 2010. Physiological responses to stress in sharks. In Sharks and their relatives II (pp. 475-506). CRC Press.

Skomal GB & Mandelman JW, 2012. The physiological response to anthropogenic stressors in marine elasmobranch fishes: a review with a focus on the secondary response. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology, 162, 146-155.

Trinanes JA, Olascoaga MJ, Goni GJ, Maximenko NA, Griffin DA & Hafner J, 2016. Analysis of flight MH370 potential debris trajectories using ocean observations and numerical model results. Journal of Operational Oceanography, 9, 126-138.

Whitenack LB, Mickley BL, Saltzman J, Kajiura SM, Macdonald CC & Shiffman DS, 2022. A content analysis of 32 years of Shark Week documentaries. PLoS One, 17, e0256842.

Worm B, Davis B, Kettemer L, Ward-Paige CA, Chapman D, Heithaus MR, Kessel ST & Gruber SH, 2013. Global catches, exploitation rates, and rebuilding options for sharks. Marine Policy, 40, 194-204.

Worm B, Orofino S, Burns ES, D’Costa NG, Manir Feitosa L, Palomares ML, Schiller L & Bradley D, 2024. Global shark fishing mortality still rising despite widespread regulatory change. Science, 383, 225-230.