The story of Alisha: how a recovered tag revealed one great white shark’s epic voyage

In 2024, a fisher in Indonesia contacted shark experts to discuss a recovered shark tag. This set in motion a chain of events that produced three startling findings: (1) that the tag had been deployed on a great white shark 12 years prior; (2) the fate of that shark years later; and (3) the incredible journey that shark took across an ocean that wouldn’t be fully appreciated until years later.

Sharks can swim very, very far

Have you ever heard the tale of a great white shark named Nicole?

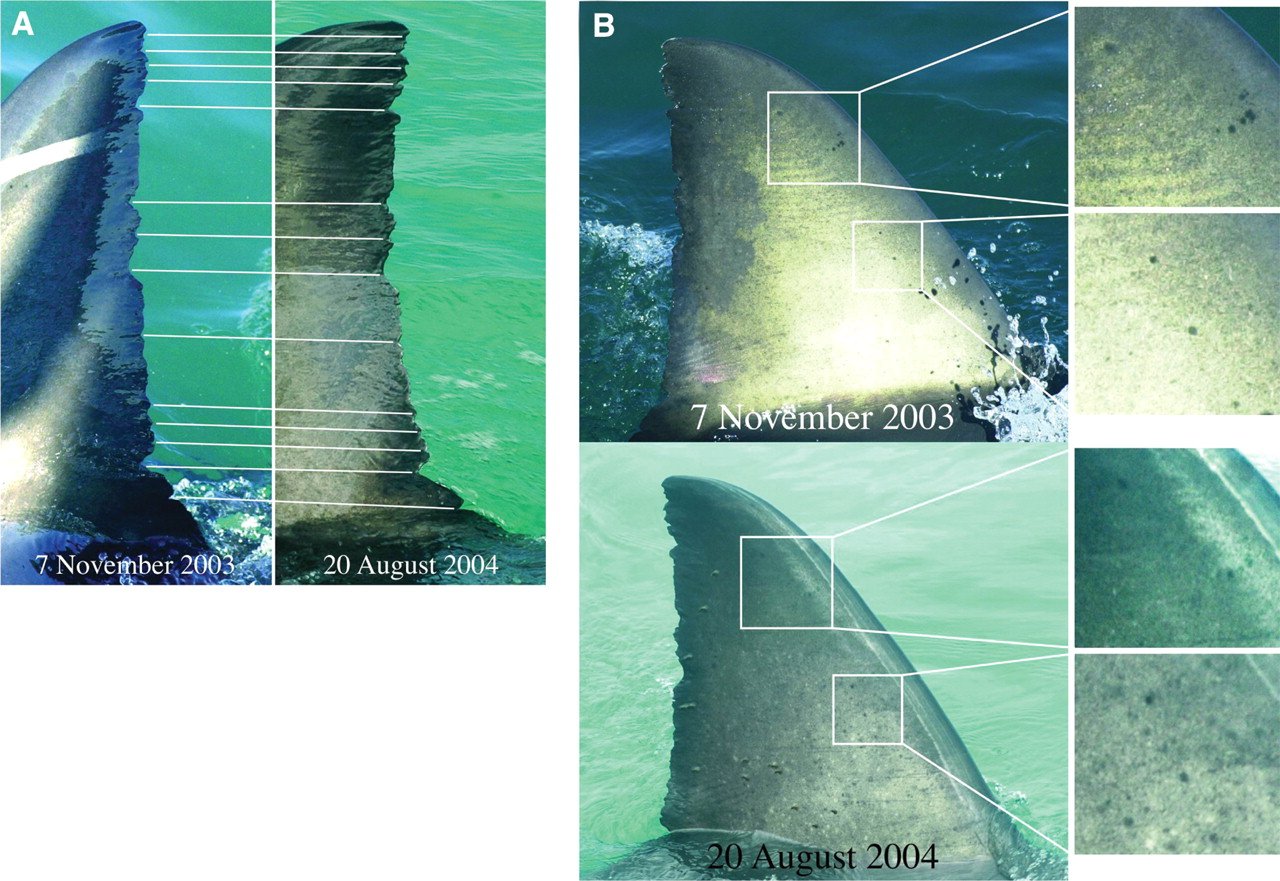

Named after Nicole Kidman, she was a 3.8 m-long female white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) that was tagged in Gansbaai, South Africa, on November 7th 2003. She was tagged with a PAT satellite tag – the PAT standing for pop-up archival transmitting. In other words, it is a tag that transmits data of a shark’s location to a satellite network as it swims before popping off after a certain length of time has passed, where it will continue to transmit and can then be recovered for analysis (Musyl et al. 2011). After being tagged, Nicole went on her merry way. It was only when her tag popped off 99 days later that her extraordinary voyage was revealed. The tag popped off nowhere near Gansbaai where she’d been tagged, or even anywhere near South Africa. No, her tag was detected on the other side of the Indian Ocean, 2 km from the coast of Australia. Yes, you read that right, Australia. In just 99 days, Nicole had travelled 11,000 km across the entire length of the Indian Ocean (Movie 1). And then, on August 20th 2004, nine months after she’d been tagged… she was back in Gansbaai! Great white sharks have unique ridge patterns on their dorsal fins akin to a fingerprint, and Nicole was identified as the same shark tagged in November based on dorsal fin photographs from November and August matching perfectly (Figure 1). To sum it up, Nicole swam from South Africa to Australia and back again. It was an incredible journey that was eventually published in Science, one of the top scientific journals in the world (Bonfil et al. 2005); and was later adapted into a book (Peirce 2017) in a rather unique legacy for a groundbreaking scientific paper on sharks.

Movie 1. A reel of Nicole’s journey from South Africa to Australia over 99 days; collated by Bonfil et al. (2025)

Figure 1. The dorsal fin of Nicole, showing markings and edge ridges confirming her identity both during her initial tagging (November 2003) and when she returned from Australia (August 2004). This figure is sourced from Figure 2 of Bonfil et al. 2005.

Nicole is the most famous ocean-travelling shark for sure, but she’s hardly the only one and the great white shark is certainly not the only species to undertake long migrations. In fact, there are several examples of sharks going on long migrations in the scientific literature (Figure 2). A 2008 study detailed a basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus) swimming almost entirely across the Atlantic Ocean over two months between the Isle of Man and Newfoundland; a journey of 9,589 km (Gore et al. 2008). Even more impressively, a whale shark (Rhincodon typus) tagged off the west coast of Panama in 2011 was recording swimming over 20,000 km across the Pacific Ocean, all the way to the Mariana Trench over the next 841 days (Guzman et al. 2018). Indeed, the same team that made this discovery identified another trans-pacific migration of a whale shark tagged in 1995 and already documented in the scientific literature (Eckhart & Stewart 2001; Guzman et al. 2018). A silky shark (Carcharhinus falciformis) tagged at the Galapagos Islands was also found to swim over 27,666 km over 546 days, reaching sites 4,755 km away from its tag site (Salinas-de-León et al. 2024). Most recently, a bull shark (Carcharhinus leucas) tagged in 2021 swam around the entire southern coast of Africa over the next three years, travelling over 7,290 km from southern Mozambique all the way around South Africa and eventually winding up off the coast of Nigeria (Daly et al. 2025). Indeed, even prehistoric sharks were likely capable of long-distance swimming. Based on calculated swim speeds and energy requirements, one of my papers hypothesised that the extinct “megalodon” shark (Otodus megalodon) was likely capable of transoceanic migrations (Cooper et al. 2022); something that was later supported by the discovery of a megalodon tooth all the way out in the middle of the Pacific Ocean with no evidence of geological transportation (Pollerspöck et al. 2023). What all of these data make clear is that sharks can swim very, very far indeed.

Figure 2. Examples of sharks migrating long distances across oceans. (a) a whale shark from Guzman et al. (2018); (b) a basking shark from Gore et al. (2008); (c) a bull shark from Daly et al. (2025); and (d) a silky shark from Salinas-de-León et al. (2024). All maps are sourced from figures within these papers.

Understanding the movements of great white sharks of South Africa, however, is particularly important at this time. That is because the South African great white shark populations are in trouble. Although there is some debate about whether the populations are declining or redistributing eastwards (Bowlby et al. 2022; 2023; 2024; Gennari et al. 2024), sightings in great white sharks have declined, particularly in the sites of False Bay, Gansbaai and Mossel Bay (Hammerschlag et al. 2019; 2025; Fisher 2021; Bowlby et al. 2023). This is likely, at least in part, due to killings of great whites in the area by killer whales (Orcinus orca), namely a pair of distinctive males named Port and Starboard (Towner et al. 2022; 2023; 2024; Cooper 2025). Additionally, sharks are caught in bait hooked drumlines along the east coast (Kock et al. 2022). Ultimately, understanding the movements of South Africa’s white sharks is essential for population management, particularly those that could be crashing as we speak.

Now, a new study (Irion et al. 2025) has unveiled the story of another great white shark’s journey; but with a very different ending to the legacy of Nicole.

Let me tell you about Alisha.

A recovered tag revealed a new epic story

In May 2024, Project Hiu, an organisation of fishing vessels in Indonesia that specialise in tagging sharks, received a SPOT-258 tag from a local fisher (Figure 3). Wanting to find out where the tag had come from, the team contacted Wildlife Computers, who revealed that it had been used to tag a 3.9 m great white shark named Alisha from South Africa in 2012 as part of a wider study (Figure 4; Kock et al. 2022). This first discovery alone was eyebrow raising: a shark from 12 years ago, tagged thousands of miles away from Indonesia. Wildlife Computers would go on to contact Ocearch and Dylan Irion, who were found to be associated with the tag in their database.

Figure 3. The recovered tag from Alisha. Photo provided by Madison Stewart.

Figure 4. Photos of Alisha’s dorsal fin (a) taken from tagging in Gansbaai, South Africa, in May 2012; (b) taken from a cage diving vessel in Gansbaai in September 2012; and (c) taken from the landing vessel in Indonesia in 2016. Sourced from Figure 1 of Irion et al. (2025).

What followed was an email chain in which the scientists took on the role of detective: what was this tag from South Africa doing all the way in Indonesia? More pressingly, where was Alisha, the shark it had come from? Following the investigations from back-and-forth email exchanges, the answers were sombering.

Tragically, it was determined that in November 2016, Alisha had been killed after being fished in Indonesian waters (Figure 4c). She had been misidentified as a 4.73 m long longfin mako shark (Isurus paucus) … despite being too big (the maximum size of I. paucus is suggested to be 4.45 m) and not having the distinctively long pectoral fins (Ebert et al. 2021). The landing had been reported to various shark scientists and to Wildlife Computers itself, but the tag had never arrived at their desk for refurbishment despite efforts to recover it. The case was cold for the next 8 years until the Indonesian fisher approached Project Hiu (Irion et al. 2025).

Madison Stewart, an award-winning conservationist and filmmaker is part of Project Hiu and was eventually one of the authors of the published paper (Irion et al. 2025) detailing the discovery of the tag and the extraordinary data extracted from it. “It was like we solved a cold case when we released this paper,” she tells me over email.

Why this Alisha’s remarkable journey is important

Despite the tragedy of Alisha’s death, the fact that she died off the Indonesian coast brings another startling revelation. The data from her recovered tag revealed that she had swam from South Africa all the way to Indonesia (Figure 5). She’d hung around South Africa for five months at first but then, in 2013, she began to swim out into the open ocean, travelling to Mozambique, to Madagascar, and finally trekking 37,178 km across the Indian Ocean over the next 395 days until she reached Indonesia (Irion et al. 2025). With a cumulative journey of such magnitude, Alisha’s swim was more than triple the length of Nicole’s journey to Australia, blowing her record swim out of the water. The fact that Alisha’s voyage and life were so abruptly cut short even after such a vast distance gives Madison a moment to reflect on what could have been. “I like to think she would have swum home based on what we saw from Nicole,” she says.

Figure 5. The journey taken by Alisha from South Africa all the way to Indonesia, connecting the two habitats. Figure sourced from Figure 2 of Irion et al. (2025).

There’s also a lot of cool science that can be taken away from Alisha’s hike. If we take the fisher recollection of her size at death (4.73 m) at face value, then it suggests she grew by 83 cm over 4.5 years (Irion et al. 2025); an average of 18.4 cm a year. Such a size and growth rate would indicate that Alisha reached sexual maturity during her voyage (Márquez-Farías et al. 2024), and her growth rate can be compared and verified against other studies that have attempted to estimate white shark growth and determine their longevity or maximum size (Cailliet et al. 1985; Bruce 2008; Tanaka et al. 2011; Hamady et al. 2014; Natanson & Skomal 2015; Christiansen et al. 2016).

The study also crucially reveals that great white shark populations between South Africa and Indonesia are connected (Irion et al. 2025), just like how South African populations are connected to Australia thanks to Nicole (Bonfil et al. 2005). This is particularly surprising as great white sharks are not actually that well documented in Indonesia (Duffy 2016). Indeed, I know of only two great white sharks reported there. One was a male white shark that was reportedly 6.6 m long (Fahmi & Dharmadi 2014), though I don’t personally buy that large a size since it was cut up into pieces before being measured (Fahmi & Dharmadi 2014) and ~6 m is considered the maximum white shark size (Randall 1973; Christiansen et al. 2014). Even the new paper suggested this particular shark was only around 6 m (Irion et al. 2025), as have white shark enthusiasts I’ve spoken to (J. S. Mierzwiak, Pers. Comm.). The second isn’t even reported in scientific literature to my knowledge, and was instead more widely reported across public media. With this newfound connectivity to South African populations (Irion et al. 2025), perhaps there are more white sharks in Indonesia than we thought. Perhaps they’ve been sighted and misidentified just like Alisha was when she was fished. Perhaps some of them have also come from South Africa, or even Australia, and thus connecting white shark populations all across the Indian Ocean.

In a grimmer takeaway, it also tells us that marine protected areas such as those in South Africa really ought to be made dynamic. Marine protected areas remaining stagnant ultimately assumes that the species living there simply stay put; but this is evidently not true in the case of the South African great white sharks – be it Nicole, Alisha or even the white sharks fleeing from killer whales (e.g., Towner et al. 2022; 2023; 2024). “I think we can get an amazing grasp of the severity of the changes in our oceans by looking at a well-established population of white sharks like those in South Africa,” Madison says, but she also notes: “discoveries like this one are so important because sharks go from an area of being protected to being completely vulnerable to fishing pressure.”

This is sadly what happened to Alisha, and there is also evidence that similar events could be happening to other sharks all over the world. Previous research has suggested that migratory ranges are being affected by climate change as species move polewards under increasing ocean temperatures (Hammerschlag et al. 2022). Indeed, we’re already seeing new species emerge in high latitudes: for example, the smalltooth sand tiger shark (Odontaspis ferox) was observed for the first time in the UK and Ireland in 2023 after the discovery of three washed up carcasses (Curnick et al. 2023). Moreover, two recent studies have revealed that migrating basking or whale sharks, particularly as they shift ranges under climate change, are vulnerable to collisions and fishing from ships in these areas where they aren’t protected (Sun et al. 2024; Womersley et al. 2024).

Most importantly, according to Madison, this work highlights the need for scientists to work more directly with local fishers. While overfishing is undoubtedly the biggest extinction threat facing sharks today (Dulvy et al. 2021; 2024), this is mostly unsustainable, large-scale, commercial fishing. In fact, local fishers in countries such as Indonesia that rely on small scale fishing for their entire livelihoods can often reveal new insights into the species that live in these areas. “We forge change from within, open the potential for scientific breakthroughs & learn from these men on a daily basis,” says Madison, who comments that the new paper’s discovery of Alisha, “helps show that.”

Ultimately, there are two takeaways from Alisha’s story. The first is a sad case of a record-breaking shark taken from the world before her impressive feat could be fully understood or appreciated by science. It potently highlights the need to improve protected areas as dynamic and how species that may be protected in one area (great white sharks have been protected in South Africa since 1991) could still be vulnerable somewhere else. This is something conservationists must consider in future as climate change forces more sharks into poleward habitats (e.g., Hammerschlag et al. 2022). The second takeaway from Alisha’s journey, however, is a lesson: one in which scientists should work with local fishing collaborators to understand relatively unexplored ocean. I suspect there are more great white sharks in Indonesia’s waters waiting to be discovered and studied; and locals like the fisher who recovered Alisha’s tag could be key for this.

“No one knows the ocean better than the man whose life depends on it,” Madison says, “I cannot talk enough on the importance of collaboration with these men. They provide an understanding that will forever remain unmatched. Not only this tag return, but by facilitating the first tagging of sharks in Indonesia, they have made so much possible.”

Acknowledgements and further reading

I deeply thank Madison Stewart of Project Hiu for answering my questions about Alisha’s epic journey, for providing me some pictures relevant to this story, and for fact checking an earlier draft of this piece. I also thank her by extension for having me on her podcast Shark Stories (twice!) to talk about megalodon. I dedicate this blog to Alisha, who sadly met her end during her travel and couldn’t be fully appreciated until long after her death. I further dedicate it to Nicole; the shark who originally traversed the Indian Ocean (Bonfil et al. 2005). I sometimes wonder where she is today; if she was fished somewhere miles away from home like Alisha, or if she may well still be swimming our seas today at a much larger size than 20 years ago. Here’s to these extraordinary sharks that change and advance science without even realising it.

You can read the full paper in Wildlife Research at:

· Irion DT, Jewell OJ, Towner AV, Fischer GC, Gennari E, Stewart M, Tyminski JP & Kock AA, 2025. Transoceanic dispersal and connectivity of a white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) between southern Africa and Southeast Asia. Wildlife Research, 52, WR24145.

You can also listen to Madison’s wonderful podcast Shark Stories at the following link. You can even hear her talking to yours truly in a couple of episodes about the megalodon: https://sharkstories.buzzsprout.com/.

Finally, you can read up on Project Hiu on their website: https://www.projecthiu.com/.

References

Bonfil R, Meÿer M, Scholl MC, Johnson R, O'Brien S, Oosthuizen H, Swanson S, Kotze D & Paterson M, 2005. Transoceanic migration, spatial dynamics, and population linkages of white sharks. Science, 310, 100-103.

Bowlby HD, Dicken ML, Towner AV, Waries S, Rogers T & Kock A, 2023. Decline or shifting distribution? A first regional trend assessment for white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) in South Africa. Ecological Indicators, 154, 110720.

Bowlby HD, Dicken ML, Towner AV, Rogers T, Waries S & Kock A, 2024. Ecological conclusions remain unchanged for white sharks in South Africa: A reply to Gennari et al. 2024. Ecological Indicators, 165, 112160.

Bowlby HD, Hammerschlag N, Irion DT & Gennari E, 2022. How continuing mortality affects recovery potential for prohibited sharks: The case of white sharks in South Africa. Frontiers in Conservation Science, 3, 988693.

Bruce BD, 2008. The biology and ecology of the white shark, Carcharodon carcharias. In Sharks of the open ocean: Biology, fisheries and conservation (pp. 69–81). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Cailliet GM, Natanson LJ, Welden BA & Ebert DA, 1985. Preliminary studies on the age and growth of the white shark, Carcharodon carcharias, using vertebral bands. Memoirs of the Southern California Academy of Sciences, 9, 49-60.

Christiansen HM, Campana SE, Fisk AT, Cliff G, Wintner SP, Dudley SF, Kerr LA & Hussey NE, 2016. Using bomb radiocarbon to estimate age and growth of the white shark, Carcharodon carcharias, from the southwestern Indian Ocean. Marine Biology, 163, 1-13.

Christiansen HM, Lin V, Tanaka S, Velikanov A, Mollet HF, Wintner SP, Fordham SV, Fisk AT & Hussey NE, 2014. The last frontier: catch records of white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) in the Northwest Pacific Ocean. PLoS One, 9, e94407.

Cooper JA, 2025. ‘Awe-inspiring and harrowing’: how two orcas with a taste for liver decimated the great white shark capital of the world. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2025/jan/23/south-africa-gansbaai-marine-biology-apex-predators-orcas-conquer-great-white-sharks-seals-penguins-trophic-cascade-aoe.

Cooper JA, Hutchinson JR, Bernvi DC, Cliff G, Wilson RP, Dicken ML, Menzel J, Wroe S, Pirlo J & Pimiento C, 2022. The extinct shark Otodus megalodon was a transoceanic superpredator: Inferences from 3D modeling. Science Advances, 8, eabm9424.

Curnick DJ, Deaville R, Bortoluzzi JR, Cameron L, Carlsson JE, Carlsson J, Dolton HR, Gordon CA, Hosegood P, Nilsson A, Perkins MW, Purves KJ, Spiro S, Vecchiato M, Williams RS & Payne NL, 2023. Northerly range expansion and first confirmed records of the smalltooth sand tiger shark, Odontaspis ferox, in the United Kingdom and Ireland. Journal of Fish Biology, 103, 1549-1555.

Daly R, Murray TS, Roberts MJ, Schoeman DS, Lubitz N, Barnett A, Cedras R, Bolaji DA, Brokensha GM, Le Noury PM, Forget F & Venables SK, 2025. Breaking barriers: Transoceanic movement by a bull shark. Ecology, 106, e70096.

Duffy CA, 2016. First record of the white shark Carcharodon carcharias (Lamniformes: Lamnidae) from Sabah, Malaysian Borneo. Marine Biodiversity Records, 9, 1-4.

Dulvy NK, Pacoureau N, Matsushiba JH, Yan HF, VanderWright WJ, Rigby CL, Finucci B, Sherman CS, Jabado RW, Carlson JK, Pollom RA, Charvet P, Pollock CM, Hilton-Taylor C & Simpfendorfer CA, 2024. Ecological erosion and expanding extinction risk of sharks and rays. Science, 386, eadn1477.

Dulvy NK, Pacoureau N, Rigby CL, Pollom RA, Jabado RW, Ebert DA, Finucci B, Pollock CM, Cheok J, Derrick DH, Herman KB, Sherman CS, VanderWright WJ, Lawson JM, Walls RHL, Carlson JK, Charvet P, Bineesh KK, Fernando D, Ralph GM, Matsushiba JH, Hilton-Taylor C, Fordham SV & Simpfendorfer CA, 2021. Overfishing drives over one-third of all sharks and rays toward a global extinction crisis. Current Biology, 31, 4773-4787.

Ebert DA, Dando M & Fowler S, 2021. Sharks of the world: a complete guide. Princeton University Press.

Eckert SA & Stewart BS, 2001. Telemetry and satellite tracking of whale sharks, Rhincodon typus, in the Sea of Cortez, Mexico, and the north Pacific Ocean. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 60, 299-308.

Fahmi & Dharmadi, 2014. First confirmed record of the white shark Carcharodon carcharias (Lamniformes: Lamnidae) from Indonesia. Marine Biodiversity Records, 7, e53.

Fisher R, 2021. Possible causes of a substantial decline in sightings in South Africa of an ecologically important apex predator, the white shark. South African Journal of Science, 117, 1-4.

Gennari E, Hammerschlag N, Andreotti S, Fallows C, Fallows M & Braccini M, 2024. Uncertainty remains for white sharks in South Africa, as population stability and redistribution cannot be concluded by Bowlby et al. (2023):“Decline or shifting distribution? a first regional trend assessment for white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) in South Africa. Ecological Indicators, 160, 111810.

Gore MA, Rowat D, Hall J, Gell FR & Ormond RF, 2008. Transatlantic migration and deep mid-ocean diving by basking shark. Biology letters, 4, 395-398.

Guzman HM, Gomez CG, Hearn A & Eckert SA, 2018. Longest recorded trans-Pacific migration of a whale shark (Rhincodon typus). Marine Biodiversity Records, 11, 1-6.

Hamady LL, Natanson LJ, Skomal GB & Thorrold SR, 2014. Vertebral bomb radiocarbon suggests extreme longevity in white sharks. PLoS One, 9, e84006.

Hammerschlag N, Herskowitz Y, Fallows C & Couto T, 2025. Evidence of cascading ecosystem effects following the loss of white sharks from False Bay, South Africa. Frontiers in Marine Science, 12, 1530362.

Hammerschlag N, McDonnell LH, Rider MJ, Street GM, Hazen EL, Natanson LJ, McCandless CT, Boudreau MR, Gallagher AJ, Pinsky ML & Kirtman B, 2022. Ocean warming alters the distributional range, migratory timing, and spatial protections of an apex predator, the tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier). Global Change Biology, 28, 1990-2005.

Hammerschlag N, Williams L, Fallows M & Fallows C, 2019. Disappearance of white sharks leads to the novel emergence of an allopatric apex predator, the sevengill shark. Scientific Reports, 9, 1908.

Irion DT, Jewell OJ, Towner AV, Fischer GC, Gennari E, Stewart M, Tyminski JP & Kock AA, 2025. Transoceanic dispersal and connectivity of a white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) between southern Africa and Southeast Asia. Wildlife Research, 52, WR24145.

Kock AA, Lombard AT, Daly R, Goodall V, Meÿer M, Johnson R, Fischer C, Koen P, Irion D, Gennari E, Towner A, Jewell OJD, da Silva C, Dicken ML, Smale MJ & Photopoulou T, 2022. Sex and size influence the spatiotemporal distribution of white sharks, with implications for interactions with fisheries and spatial management in the Southwest Indian Ocean. Frontiers in Marine Science, 9, 811985.

Márquez-Farías JF, Tyminski JP, Fischer GC & Hueter RE, 2024. Length at life stages of the white shark Carcharodon carcharias in the western North Atlantic. Endangered Species Research, 53, 199-211.

Musyl MK, Domeier ML, Nasby-Lucas N, Brill RW, McNaughton LM, Swimmer JY, Lutcavage MS, Wilson SG, Galuardi B & Liddle JB, 2011. Performance of pop-up satellite archival tags. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 433, 1-28.

Natanson LJ & Skomal GB, 2015. Age and growth of the white shark, Carcharodon carcharias, in the western North Atlantic Ocean. Marine and Freshwater Research, 66, 387-398.

Peirce R, 2017. Nicole: the true story of a great white shark’s journey into history. Struik Nature.

Pollerspöck J, Cares D, Ebert DA, Kelley KA, Pockalny R, Robinson RS, Wagner D & Straube N, 2023. First in situ documentation of a fossil tooth of the megatooth shark Otodus (Megaselachus) megalodon from the deep sea in the Pacific Ocean. Historical Biology, 37, 120-125.

Randall JE, 1973. Size of the great white shark (Carcharodon). Science, 181, 169-170.

Salinas‐de‐León P, Vaudo J, Logan R, Suarez‐Moncada J & Shivji M, 2024. Longest recorded migration of a silky shark (Carcharhinus falciformis) reveals extensive use of international waters of the Tropical Eastern Pacific. Journal of Fish Biology, 105, 378-381.

Sun R, Liu K, Huang W, Wang X, Zhuang H, Wang Z, Zhang Z & Zhao L, 2024. Global distribution prediction and ecological conservation of basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus) under integrated impacts. Global Ecology and Conservation, 56, e03310.

Tanaka S, Kitamura T, Mochizuki T & Kofuji K, 2011. Age, growth and genetic status of the white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) from Kashima-nada, Japan. Marine and Freshwater Research, 62, 548-556.

Towner AV, Kock AA, Stopforth C, Hurwitz D & Elwen SH, 2023. Direct observation of killer whales preying on white sharks and evidence of a flight response. Ecology, 104, e3875.

Towner A, Micarelli P, Hurwitz D, Smale MJ, Booth AJ, Stopforth C, Jacobs E, Reinero FR, Ricci V, Di Bari A, Gavazzi S, Caurgno G, Mahrer M & Gennari E, 2024. Further insights into killer whales Orcinus orca preying on white sharks Carcharodon carcharias in South Africa. African Journal of Marine Science, 46, 1-5.

Towner AV, Watson RGA, Kock AA, Papastamatiou Y, Sturup M, Gennari E, Baker K, Booth T, Dicken M, Chivell W, Elwen S, Kaschke T, Edwards D & Smale M, 2022. Fear at the top: killer whale predation drives white shark absence at South Africa’s largest aggregation site. African Journal of Marine Science, 44, 139-152.

Womersley FC, Sousa LL, Humphries NE, Abrantes K, Araujo G, Bach SS, Barnett A, Berumen ML, Lion SB, Braun CD, Clingham E, Cochran JEM, de la Parra R, Diamant S, Dove ADM, Duarte CM, Dudgeon CL, Erdmann MV, Espinoza E, Ferreira LC, Fitzpatrick R, Cano JG, Green JR, Guzman HM, Hardenstine R, Hasan A, Hazin FHV, Hearn AR, Hueter RE, Jaidah MY, Labaja J, Ladino F, Macena BCL, Meekan MG, Morris Jr JJ, Norman BM, Peñaherrera-Palma CR, Pierce SJ, Quintero LM, Ramírez-Macías D, Reynolds SD, Robinson DP, Rohner CA, Rowat DRL, Sequeria AMM, Sheaves M, Shivji MS, Sianipar AB, Skomal GB, Soler G, Syakurachman I, Thorrold SR, Thums M, Tyminski JP, Webb DH, Wetherbee BM, Queiroz N & Sims DW, 2024. Climate-driven global redistribution of an ocean giant predicts increased threat from shipping. Nature Climate Change, 14, 1282-1291.